Kidney transplant: New opportunities and challenges

ABSTRACT

Progress in kidney transplant has improved survival while creating challenges. The pool of eligible patients is increasing, but organ supply remains inadequate. Waiting-list issues, adequate pretransplant assessment, judicious use of potent immunotherapy, and management of infections must be considered.

KEY POINTS

- Kidney transplant improves survival and long-term outcomes in patients with renal failure.

- Before transplant, patients should be carefully evaluated for cardiovascular and infectious disease risk.

- Potent immunosuppression is required to maintain a successful kidney transplant.

- After transplant, patients must be monitored for recurrent disease, side effects of immunosuppression, and opportunistic infections.

Reduced long-term risk of myocardial infarction after transplant

Kasiske et al10 analyzed data from more than 50,000 patients from the US Renal Data System and found that, for about the first year after transplant, patients who underwent kidney transplant were more likely to have a myocardial infarction than those on dialysis. After that, they fared better than patients who remained on dialysis. Those with a living-donor transplant were less likely at all times to have a myocardial infarction than those with a deceased-donor transplant. By 3 years after transplant, the relative risk of having a myocardial infarction was 0.89 for deceased-donor organ recipients and 0.69 for living-donor recipients compared with patients on the waiting list.10

INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS IN KIDNEY RECIPIENTS

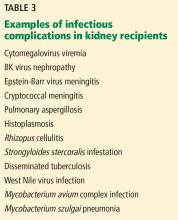

Kidney recipients are prone to many common and uncommon infections (Table 3). All potential recipients are tested pretransplant for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, and tuberculosis. A positive result does not necessarily rule out transplant.

The following viral serology tests are also done before transplant:

Epstein-Barr virus (antibodies are positive in about 90% of adults)

CMV (about 70% of adults are seropositive)

Varicella zoster (seronegative patients should be given live-attenuated varicella vaccine).

Risk of transmission of these viruses relates to the serostatus of the donor and recipient before transplant. If a donor is positive for viral antibodies but the recipient is not (a so-called “mismatch”), risk is higher after transplant.

Hepatitis C

Patients with hepatitis C fare better if they get a transplant than if they remain on dialysis, although their posttransplant course is worse compared with transplant patients who do not have hepatitis. Some patients develop accelerated liver disease after kidney transplant. Hepatitis C-related kidney disease—membranous proliferative glomerulonephritis—also occurs, as do comorbidities such as diabetes.

Careful evaluation is warranted before transplant, including liver imaging, alpha-fetoprotein testing, and liver biopsy to evaluate for hepatocellular carcinoma. A patient with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis may not be a candidate for kidney transplant alone but could possibly receive a combined kidney and liver transplant.

There is a need to determine the best time to treat hepatitis C infection. Patients with advanced liver disease or hepatitis C-related kidney disease would likely benefit from early treatment. However, delaying treatment could shorten the wait time for a deceased-donor organ positive for hepatitis C. Transplant candidates with active hepatitis C are uniquely considered to accept hepatitis C-positive kidneys, which are often discarded, and may only wait weeks for such a transplant. The shortened kidney survival associated with a hepatitis C-positive kidney may no longer be true with the new antiviral hepatitis C therapy, which has been shown to be effective post-transplant.

Hepatitis B

No cure is available for hepatitis B infection, but it can be well controlled with antiviral therapy. Patients with hepatitis B infection may be candidates for transplant, but they should be stable on antiviral therapy (lamivudine, entecavir, or tenofovir) to eliminate the viral load before transplant, and therapy should be continued afterward. Liver imaging, alpha-fetoprotein levels, and biopsy are recommended for evaluation. All hepatitis B- negative patients should be vaccinated before transplant.

Organs from living or deceased donors that test positive for hepatitis B core antibody, indicating prior exposure, can be considered for transplant in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B surface antibody, indicating successful vaccination or prior exposure in the recipient. But donors must have negative surface antigen and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests that indicate no active hepatitis B infection.

Cytomegalovirus

CMV typically does not appear until prophylactic therapy is stopped. Classic symptoms are fever, leukopenia, and diarrhea. Infection can involve any organ, and patients may present with hepatitis, pancreatitis or, less commonly, pneumonitis.

Patients who are negative for CMV before transplant and receive a donor-positive organ are at the highest risk. Patients who are CMV IgG-positive are considered to be at intermediate risk, regardless of the donor status. Patients who are negative for CMV and receive a donor-negative organ are at the lowest risk and do not need prophylaxis with valganciclovir.

CMV infection is diagnosed by PCR testing of the blood or immunostaining in tissue biopsy. Occasionally, blood testing is negative in the face of tissue-based disease.

BK virus

BK is a polyoma virus and a common virus associated with kidney transplant. Viremia is seen in about 18% of patients, whereas actual kidney disease associated with a higher level of virus is seen in fewer than 10% of patients. Most people are exposed to BK virus, often in childhood, and it can remain indolent in the bladder and uroepithelium.

Patients can develop BK nephropathy after exposure to transplant immunosuppression.11 Posttransplant monitoring protocols typically include PCR testing for BK virus at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. No agent has been identified to specifically treat BK virus. The general strategy is to minimize immunosuppressive therapy by reducing or eliminating mycophenolate mofetil. Fortunately, BK virus does not tend to recur, and patients can have a low-level viremia (< 10,000 copies/mL) persisting over months or even years but often without clinical consequences.

The appearance of BK virus on biopsy can mimic acute rejection. Before BK viral nephropathy was a recognized entity, patients would have been diagnosed with acute rejection and may have been put on high-dose steroids, which would have worsened the BK infection.

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder is most often associated with Epstein-Barr virus and usually involves a large, diffuse B-cell lymphoma. Burkitt lymphoma and plasma cell neoplasms also can occur less commonly.

The condition is about 30 times more common in patients after transplant than in the general population, and it is the third most common malignancy in transplant patients after skin and cervical cancers. About 80% of the cases occur early after transplant, within the first year.

Patients typically have a marked elevation in viral load of Epstein-Barr virus, although a negative viral load does not rule it out. A patient who is serologically negative for Epstein-Barr virus receiving a donor-positive kidney is at highest risk; this situation is most often seen in the pediatric population. Potent induction therapies (eg, antilymphocyte antibody therapy) are also associated with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Patients typically present with fever of unknown origin with no localizing signs or symptoms. Mass lesions can be challenging to find; positron emission tomography may be helpful. The culprit is usually a focal mass, ulcer (especially in the gastrointestinal tract), or infiltrate (commonly localized to the allograft). Multifocal or disseminated disease can also occur, including lymphoma or with central nervous system, gastrointestinal, or pulmonary involvement.

Biopsy of the affected site is required for histopathology and Epstein-Barr virus markers. PCR blood testing is often positive for Epstein-Barr virus.

Typical antiviral therapy does not eliminate Epstein-Barr virus. In early polyclonal viral proliferation, the first goal is to reduce immunosuppressive therapy. Rituximab alone may also help in polymorphic cases. With disease that is clearly monomorphic and has transformed to a true malignancy, cytotoxic chemotherapy is also required. “R-CHOP,” a combination therapy consisting of rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, is usually used. Radiation therapy may help in some cases.

Cryptococcal infection

Previously seen in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome, cryptococcal infection is now most commonly encountered in patients with solid-organ transplants. Vilchez et al12 found a 1% incidence in a series of more than 5,000 patients who had received an organ transplant.

Immunosuppression likely conveys risk, but because cryptococcal infection is acquired, environmental exposure also plays a role. It tends to appear more than 6 months after transplant, indicating that its cause is a primary infection by spore inhalation rather than by reactivation or transmission from the donor organ.13 Bird exposure is a risk factor for cryptococcal infection. One case identified the same strain of Cryptococcus in a kidney transplant recipient and the family’s pet cockatoo.14

Cryptococcal infection typically starts as pneumonia, which may be subclinical. The infection can then disseminate, with meningitis presenting with headache and mental status changes being the most concerning complication. The death rate is about 50% in most series of patients with meningitis. Skin and soft-tissue manifestations may also occur in 10% to 15% of cases and can be nodular, ulcerative, or cellulitic.

More than 75% of fungal infections requiring hospitalization in US patients who have undergone transplant are attributed to either Candida, Aspergillus, or Cryptococcus species.15 Risk of fungal infection is increased with diabetes, duration of pretransplant dialysis, tacrolimus therapy, or rejection treatment.