Clinical presentation and imaging of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas

ABSTRACT

The clinical presentation of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas is varied. Constitutional symptoms are rare, and although bone sarcomas tend to be painful while soft-tissue sarcomas usually are not, there are exceptions to this general rule. A high index of suspicion is required for any unexplained mass with indeterminate imaging findings. Choosing the right imaging modality is critical to the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected sarcoma, and referring clinicians have a multitude of imaging options. After discovery of a malignant-appearing bone lesion by radiography, further imaging is obtained for better characterization of the lesion (typically with magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) and for staging (typically with computed tomography of the chest). In contrast, radiographs are rarely helpful for evaluation of soft-tissue lesions, which almost always require MRI assessment.

CROSS-SECTIONAL IMAGING WITH MRI AND CT

MRI preferred for evaluation of most masses

MRI is the examination of choice in the evaluation of soft-tissue masses in light of its superior contrast resolution and ability to demonstrate subtle changes in soft tissues.

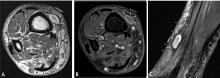

Predicting the histology of most soft-tissue masses is difficult, with the exception of some benign vascular lesions (eg, hemangioma), ganglia, neurogenic lesions, and well-differentiated lipomatous lesions. Aggressive features of a soft-tissue neoplasm include size greater than 5 cm,15 deep location, and absence of central enhancement, which is suggestive of necrosis (Figure 1). Yet one third of soft-tissue sarcomas are either superficial or smaller than 5 cm, which highlights the relative nonspecificity of these features.15

MRI is also the preferred modality in the evaluation of the majority of bone sarcomas, given its ability to accurately define the extent of marrow changes and soft-tissue involvement. MRI should be performed prior to a biopsy to prevent misinterpretation of biopsy-related signal changes in the surrounding tissues, which may negate the value of MRI in sarcoma staging.

Several distinct roles for CT

Chest CT should be obtained in all cases of known malignant neoplasms to evaluate for pulmonary nodules, masses, and lymphadenopathy. Despite the recent advances in MRI, CT remains the imaging modality of choice to evaluate the retroperitoneum, abdomen, and pelvis for masses, lymphadenopathy, or other signs of metastatic disease.

Post-treatment monitoring for recurrence

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography has a limited role in the initial diagnosis and follow-up of musculoskeletal tumors. Its main advantages are a lack of ionizing radiation and dynamic imaging capabilities. Doppler ultrasonography allows direct visualization of tumor vascularity, which may be important for diagnosis and presurgical planning. Unfortunately, bone lesions cannot be evaluated with ultrasonography, owing to the inability of sound waves to penetrate the bony cortex. Poor sound wave penetration may prevent visualization of deep-seated lesions, such as retroperitoneal sarcomas.

Ultrasonography is best used for differentiating solid masses from cystic structures and can provide image guidance in solid tumor biopsy and cyst aspiration. It also may play a role in detecting suspected tumor recurrence in patients in whom artifact from implanted hardware precludes cross-sectional imaging, and it can be reliably used for following up unequivocal soft-tissue masses such as ganglia near joints.

POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY

IMAGING-GUIDED INTERVENTIONS

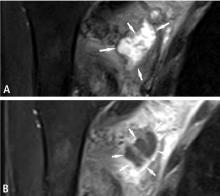

Percutaneous imaging-guided procedures have increasingly replaced open surgical biopsies for bone and soft-tissue tumors. CT guidance is commonly used for percutaneous biopsy, whereas ultrasonographic guidance is sometimes used for superficial soft-tissue lesions. Although the shortest and most direct approach is desirable, this may not be possible in all cases due to the presence of nearby vital structures or the risk of contamination. Seeding of malignant cells along the biopsy tract is a well-known possible complication of image-guided biopsies, and en bloc resection of the needle tract is typically performed at the definitive surgery.

Knowledge of compartmental anatomy is paramount in planning the approach for these biopsies, and consultation with the referring orthopedic surgeon is recommended for optimal management. Expert histopathological interpretation of bone and soft-tissue specimens is essential for the efficacy and high success rates of percutaneous imaging-guided biopsies. Such expertise is integral to the broader interdisciplinary collaboration that is needed to arrive at the most plausible diagnosis, especially in the setting of uncommon or atypical neoplasms.

Currently, MRI-guided interventions are in the initial stage of evolution and could provide valuable guidance for subtle marrow or soft-tissue lesions visible on MRI but not well seen on CT.22 In the future, MRI could play an increasingly important role in imaging-guided procedures because of its lack of ionizing radiation and its ability to demonstrate subtle soft-tissue and bone marrow changes. Imaging-guided therapeutics are growing in their applications in musculoskeletal oncology. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation have been used in the treatment of a variety of tumors23 as well as in the palliation of metastatic bone pain.24

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Bone and soft-tissue sarcomas are rare neoplasms with variable clinical presentations. A high index of suspicion is required for any unexplained mass with indeterminate imaging findings. Recent advances in imaging technology, including cross-sectional MRI and CT, have significantly refined the diagnosis and management of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. When faced with a possible sarcoma, the clinician’s selection of imaging modalities has a direct impact on diagnosis, staging, and patient management.