High users of healthcare: Strategies to improve care, reduce costs

ABSTRACT

A minority of patients consume a disproportionate amount of healthcare, especially in the emergency department. These “high users” are a small but complex group whose expenses are driven largely by low socioeconomic status, mental illness, and drug abuse; lack of social services also contributes. Several promising efforts aimed at improving quality and reducing healthcare costs for high users include care management organizations, patient care plans, and better discharge summaries.

KEY POINTS

- The top 5% of the population in terms of healthcare use account for 50% of costs. The top 1% account for 23% of all expenditures and cost 10 times more per year than the average patient.

- Drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty often accompany and underlie high-use behavior, particularly in patients without end-stage medical conditions.

- Comprehensive patient care plans and care management organizations are among the most effective strategies for cost reduction and quality improvement.

Effective models

In 1998, the Camden (NJ) Coalition of Healthcare Providers established a model for CMO care plans. Starting with the first 36 patients enrolled in the program, hospital admissions and emergency department visits were cut by 47% (from 62 to 37 per month), and collective hospital costs were cut by 56% (from $1.2 million to about $500,000 per month).8 It should be noted that this was a small, nonrandomized study and these preliminary numbers did not take into account the cost of outpatient physician visits or new medications. Thus, how much money this program actually saves is not clear.

Similar programs have had similar results. A nurse-led care coordination program in Doylestown, PA, showed an impressive 25% reduction in annual mortality and a 36% reduction in overall costs during a 10-year period.9

A program in Atlantic City, NJ, combined the typical CMO model with a primary care clinic to provide high users with unlimited access, while paying its providers in a capitation model (as opposed to fee for service). It achieved a 40% reduction in yearly emergency department visits and hospital admissions.8

Patient care plans

Individualized patient care plans for high users are among the most promising tools for reducing costs and improving quality in this group. They are low-cost and relatively easy to implement. The goal of these care plans is to provide practitioners with a concise care summary to help them make rational and consistent medical decisions.

Typically, a care plan is written by an interdisciplinary committee composed of physicians, nurses, and social workers. It is based on the patient’s pertinent medical and psychiatric history, which may include recent imaging results or other relevant diagnostic tests. It provides suggestions for managing complex chronic issues, such as drug abuse, that lead to high use of healthcare resources.

These care plans provide a rational and prespecified approach to workup and management, typically including a narcotic prescription protocol, regardless of the setting or the number of providers who see the patient. Practitioners guided by effective care plans are much more likely to effectively navigate a complex patient encounter as opposed to looking through extensive medical notes and hoping to find relevant information.

Effective models

Data show these plans can be effective. For example, Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, implemented patient care plans in 2010. During the first 4 months, hospital admissions in the first 94 patients were reduced by 67%.10

A study of high users at Duke University Medical Center reported similar results. One year after starting care plans, inpatient admissions had decreased by 50.5%, readmissions had decreased by 51.5%, and variable direct costs per admission were reduced by 35.8%. Paradoxically, emergency department visits went up, but this anomaly was driven by 134 visits incurred by a single dialysis patient. After removing this patient from the data, emergency department visits were relatively stable.4

Better discharge summaries

Although improving discharge summaries is not a novel concept, changing the summary from a historical document to a proactive discharge plan has the potential to prevent readmissions and promote a durable de-escalation in care acuity.

For example, when moving a patient to a subacute care facility, providing a concise summary of which treatments worked and which did not, a list of comorbidities, and a list of medications and strategies to consider, can help the next providers to better target their plan of care. Studies have shown that nearly half of discharge statements lack important information on treatments and tests.11

Improvement can be as simple as encouraging practitioners to construct their summaries in an “if-then” format. Instead of noting for instance that “Mr. Smith was treated for pneumonia with antibiotics and discharged to a rehab facility,” the following would be more useful: “Family would like to see if Mr. Smith can get back to his functional baseline after his acute pneumonia. If he clinically does not do well over the next 1 to 2 weeks and has a poor quality of life, then family would like to pursue hospice.”

In addition to shifting the philosophy, we believe that providing timely discharge summaries is a fundamental, high-yield aspect of ensuring their effectiveness. As an example, patients being discharged to a skilled nursing facility should have a discharge summary completed and in hand before leaving the hospital.

Evidence suggests that timely writing of discharge summaries improves their quality. In a retrospective cohort study published in 2012, discharge summaries created more than 24 hours after discharge were less likely to include important plan-of-care components.12

FUTURE NEEDS

Randomized trials

Although initial results have been promising for the strategies outlined above, much of the apparent cost reduction of these interventions may be at least partially related to the study design as opposed to the interventions themselves.

For example, Hong et al13 examined 18 of the more promising CMOs that had reported initial cost savings. Of these, only 4 had conducted randomized controlled trials. When broken down further, the initial cost reduction reported by most of these randomized controlled trials was generated primarily by small subgroups.14

These results, however, do not necessarily reflect an inherent failure in the system. We contend that they merely demonstrate that CMOs and care plan administrators need to be more selective about whom they enroll, either by targeting patients at the extremes of the usage curve or by identifying patient characteristics and usage parameters amenable to cost reduction and quality improvement strategies.

Better social infrastructure

Although patient care plans and CMOs have been effective in managing high users, we believe that the most promising quality improvement and cost-reduction strategy involves redirecting much of the expensive healthcare spending to the social determinants of health (eg, homelessness, mental illness, low socioeconomic status).

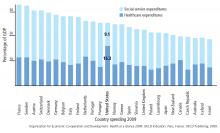

Among developed countries, the United States has the highest healthcare spending and the lowest social service spending as a percentage of its gross domestic product (Figure 1).15 Although seemingly discouraging, these data can actually be interpreted as hopeful, as they support the notion that the inefficiencies of our current system are not part of an inescapable reality, but rather reflect a system that has evolved uniquely in this country.

Using the available social programs

Exemplifying this medical and social services balance is a high user who visited her local emergency department 450 times in 1 year for reasons primarily related to homelessness.16 Each time, the medical system (as it is currently designed to do) applied a short-term medical solution to this patient’s problems and discharged her home, ie, back to the street.

But this patient’s high use was really a manifestation of a deeper social issue: homelessness. When the medical staff eventually noted how much this lack of stable shelter was contributing to her pattern of use, she was referred to appropriate social resources and provided with the housing she needed. Her hospital visits decreased from 450 to 12 in the subsequent year, amounting to a huge cost reduction and a clear improvement in her quality of life.

Similar encouraging results have resulted when available social programs are applied to the high-use population at large, which is particularly reassuring given this population’s preponderance of low socioeconomic status, mental illness, and homelessness. (The prevalence of homelessness is roughly 20%, depending on the definition of a high user).

New York Medicaid, for example, has a housing program that provides stable shelter outside of acute care medical settings for patients at a rate as low as $50 per day, compared with area hospital costs that often exceed $2,200 daily.17 A similar program in Westchester County, NY, reported a 45.9% reduction in inpatient costs and a 15.4% reduction in emergency department visits among 61 of its highest users after 2 years of enrollment.17

Need to reform privacy laws

Although legally daunting, reform of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other privacy laws in favor of a more open model of information sharing, particularly for high-risk patients, holds great opportunity for quality improvement. For patients who obtain their care from several healthcare facilities, the documentation is often inscrutable. If some of the HIPAA regulations and other patient privacy laws were exchanged for rules more akin to the current model of narcotic prescription tracking, for example, physicians would be better equipped to provide safe, organized, and efficient medical care for high-use patients.

Need to reform the system

A fundamental flaw in our healthcare system, which is largely based on a fee-for-service model, is that it was not designed for patients who use the system at the highest frequency and greatest cost. Also, it does not account for the psychosocial factors that beset many high-use patients. As such, it is imperative for the safety of our patients as well as the viability of the healthcare system that we change our historical way of thinking and reform this system that provides high users with care that is high-cost, low-quality, and not patient-centered.

IMPROVING QUALITY, REDUCING COST

High users of emergency services are a medically and socially complex group, predominantly characterized by low socioeconomic status and high rates of mental illness and drug dependency. Despite their increased healthcare use, they do not have better outcomes even though they are not sicker. Improving those outcomes requires both medical and social efforts.

Among the effective medical efforts are strategies aimed at creating individualized patient care plans, using coordinated care teams, and improving discharge summaries. Addressing patients’ social factors, such as homelessness, is more difficult, but healthcare systems can help patients navigate the available social programs. These strategies are part of a comprehensive care plan that can help reduce the cost and improve the quality of healthcare for high users.