Preventing cardiovascular disease in older adults: One size does not fit all

ABSTRACT

Frailty and cardiovascular disease are highly interconnected and increase in prevalence with age. Identifying frailty allows for a personalized cardiovascular risk prescription and individualized management of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and lifestyle in the aging population.

KEY POINTS

- With the aging of the population, individualized prevention strategies must incorporate geriatric syndromes such as frailty.

- However, current guidelines and available evidence for cardiovascular disease prevention strategies have not incorporated frailty or make no recommendation at all for those over age 75.

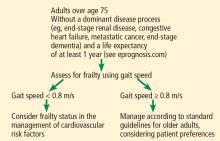

- Four-meter gait speed, a simple measure of physical function and a proxy for frailty, can be used clinically to diagnose frailty.

ASSESSING FRAILTY IN THE CLINIC

For adults over age 70, frailty assessment is an important first step in managing cardiovascular disease risk.15 Frailty status will better identify those at risk of adverse outcomes in the short term and those who are most likely to benefit from long-term cardiovascular preventive strategies. Additionally, incorporating frailty assessment into traditional risk factor evaluation may permit appropriate intervention and prevention of a potentially modifiable risk factor.

Gait speed is a quick, easy, inexpensive, and sensitive way to assess frailty status, with excellent inter-rater and test-retest reliability, even in those with cognitive impairment.16 Slow gait speed predicts limitations in mobility, limitations in activities of daily living, and death.8,17

In a prospective study18 of 1,567 men and women, mean age 74, slow gait speed was the strongest predictor of subsequent cardiovascular events.18

Gait speed is usually measured over a distance of 4 meters (13.1 feet),17 and the patient is asked to walk comfortably in an unobstructed, marked area. An assistive walking device can be used if needed. If possible, this is repeated once after a brief recovery period, and the average is recorded.

The FRAIL scale19,20 is a simple, validated questionnaire that combines the Fried and Rockwood concepts of frailty and can be given over the phone or to patients in a waiting room. One point is given for each of the following, and people who have 3 or more are considered frail:

- Fatigue

- Resistance (inability to climb 1 flight of stairs)

- Ambulation (inability to walk 1 block)

- Illnesses (having more than 5)

- Loss of more than 5% of body weight.

Other measures of physical function such as grip strength (using a dynamometer), the Timed Up and Go test (assessing the ability to get up from a chair and walk a short distance), and Short Physical Performance Battery (assessing balance, chair stands, and walking speed) can be used to screen for frailty, but are more time-intensive than gait speed alone, and so are not always practical to use in a busy clinic.21

MANAGEMENT OF RISK FACTORS

Management of cardiovascular risk factors is best individualized as outlined below.

LOWERING HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

The incidence of ischemic heart disease and stroke increases with age across all levels of elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure.22 Hypertension is also associated with increased risk of cognitive decline. However, a J-shaped relationship has been observed in older adults, with increased cardiovascular events for both low and elevated blood pressure, although the clinical relevance remains controversial.23

Odden et al24 performed an observational study and found that high blood pressure was associated with an increased mortality rate in older adults with normal gait speed, while in those with slow gait speed, high blood pressure neither harmed nor helped. Those who could not walk 6 meters appeared to benefit from higher blood pressure.

HYVET (the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial),25 a randomized controlled trial in 3,845 community-dwelling people age 80 or older with sustained systolic blood pressure higher than 160 mm Hg, found a significant reduction in rates of stroke and all-cause mortality (relative risk [RR] 0.76, P = .007) in the treatment arm using indapamide with perindopril if necessary to reach a target blood pressure of 150/80 mm Hg.

Frailty was not assessed during the trial; however, in a reanalysis, the results did not change in those identified as frail using a Rockwood frailty index (a count of health-related deficits accumulated over the lifespan).26

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial)27 randomized participants age 50 and older with systolic blood pressure of 130 to 180 mm Hg and at increased risk of cardiovascular disease to intensive treatment (goal systolic blood pressure ≤ 120 mm Hg) or standard treatment (goal systolic blood pressure ≤ 140 mm Hg). In a prespecified subgroup of 2,636 participants over age 75 (mean age 80), hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for adverse outcomes with intensive treatment were:

- Major cardiovascular events: HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.51–0.85

- Death: HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.49–0.91.

Over 3 years of treatment this translated into a number needed to treat of 27 to prevent 1 cardiovascular event and 41 to prevent 1 death.

Within this subgroup, the benefit was similar regardless of level of frailty (measured both by a Rockwood frailty index and by gait speed).

However, the incidence of serious adverse treatment effects such as hypotension, orthostasis, electrolyte abnormalities, and acute kidney injury was higher with intensive treatment in the frail group. Although the difference was not statistically significant, it is cause for caution. Further, the exclusion criteria (history of diabetes, heart failure, dementia, stroke, weight loss of > 10%, nursing home residence) make it difficult to generalize the SPRINT findings to the general aging population.27

Tinetti et al28 performed an observational study using a nationally representative sample of older adults. They found that receiving any antihypertensive therapy was associated with an increased risk of falls with serious adverse outcomes. The risks of adverse events related to antihypertensive therapy increased with age.