Chronic kidney disease in African Americans: Puzzle pieces are falling into place

ABSTRACT

Recent decades have seen great advances in the understanding of chronic kidney disease, spurred by standardizing disease definitions and large-scale patient surveillance. African Americans are disproportionately affected by the disease, and recently discovered genetic variants in APOL1 that protect against sleeping sickness in Africa provide an important explanation for the increased burden. Studies are now under way to determine if genetic testing of African American transplant donors and recipients is advisable.

KEY POINTS

- Patients with chronic kidney disease are more likely to die than to progress to end-stage disease, and cardiovascular disease and cancer are the leading causes of death.

- As kidney function declines, the chance of dying from cardiovascular disease increases.

- African Americans tend to develop kidney disease at a younger age than whites and are much more likely to progress to dialysis.

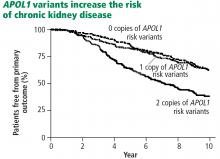

- About 15% of African Americans are homozygous for a variant of the APOL1 gene. They are more likely to develop kidney disease and to have worse outcomes.

GENETIC VARIANTS FOUND

In 2010, two variant alleles of the APOL1 gene on chromosome 22 were found to be associated with nondiabetic kidney disease.15 Three nephropathies are associated with being homozygous for these alleles:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, the leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in African Americans

- Hypertension-associated kidney disease with scarring of glomeruli in vessels, the primary cause of end-stage renal disease in African Americans

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)- associated nephropathy, usually a focal segmental glomerulosclerosis type of lesion.

The first two conditions are about 3 to 5 times more prevalent in African Americans than in whites, and HIV-associated nephropathy is about 20 to 30 times more common.

African sleeping sickness and chronic kidney disease

Retrospective analysis of biologic samples from trials of kidney disease in African Americans has revealed interesting results.

The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) observation study18 enrolled patients with an estimated GFR of 20 to 70 mL/min/1.73 m2, with a preference for African Americans and patients with diabetes. Nearly 3,000 participants had adequate samples for DNA testing. They found that African Americans with the double variant allele had worse outcomes, whether or not they had diabetes, compared with whites and African Americans without the homozygous gene variant.

Mechanism not well understood

The mechanism of renal injury is not well understood. Apolipoprotein L1, the protein coded for by APOL1, is a component of high-density lipoprotein. It is found in a different distribution pattern in people with normal kidneys vs those with nondiabetic kidney disease, especially in the arteries, arterioles, and podocytes.19,20 It can be detected in blood plasma, but levels do not correlate with kidney disease.21 Not all patients with the high-risk variant develop chronic kidney disease; a “second hit” such as infection with HIV may be required.

Investigators have recently developed knockout mouse models of APOL1-associated kidney diseases that are helping to elucidate mechanisms.22,23

EFFECT OF GENOTYPE ON KIDNEY TRANSPLANTS IN AFRICAN AMERICANS

African Americans receive about 30% of kidney transplants in the United States and represent about 15% to 20% of all donors.

Lee et al24 reviewed 119 African American recipients of kidney transplants, about half of whom were homozygous for an APOL1 variant. After 5 years, no differences were found in allograft survival between recipients with 0, 1, or 2 risk alleles.

However, looking at the issue from the other side, Reeves-Daniel et al25 studied the fate of more than 100 kidneys that were transplanted from African American donors, 16% of whom had the high-risk, homozygous genotype. In this case, graft failure was much likelier to occur with the high-risk donor kidneys (hazard ratio 3.84, P = .008). Similar outcomes were shown in a study of 2 centers26 involving 675 transplants from deceased donors, 15% of which involved the high-risk genotype. The hazard ratio for graft failure was found to be 2.26 (P = .001) with high-risk donor kidneys.

These studies, which examined data from about 5 years after transplant, found that kidney failure does not tend to occur immediately in all cases, but gradually over time. Most high-risk kidneys were not lost within the 5 years of the studies.

The fact that the high-risk kidneys do not all fail immediately also suggests that a second hit is required for failure. Culprits postulated include a bacterial or viral infection (eg, BK virus, cytomegalovirus), ischemia or reperfusion injury, drug toxicity, and immune-mediated allograft injury (ie, rejection).