2017 Update in perioperative medicine: 6 questions answered

ABSTRACT

The authors performed a MEDLINE search to identify articles published between January 2016 and April 2017 that had significant impact on perioperative care. They identified 6 topics for discussion.

KEY POINTS

- Noncardiac surgery after drug-eluting stent placement can be considered after 3 to 6 months for those with greater surgical need and lower risk of stent thrombosis.

- Perioperative statin use continues to show benefits with minimal risk in large cohort studies, but significant randomized controlled trial data are lacking.

- Patients should be screened for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery, and further cardiopulmonary testing should be performed if the patient has evidence of significant sequelae from obstructive sleep apnea.

- For patients with atrial fibrillation on vitamin K antagonists, bridging can be considered for those with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 5 or 6 and a history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic thromboembolism. Direct oral anticoagulation should not be bridged.

- Frailty carries significant perioperative mortality risk; systems-based changes to minimize these patients’ risks can be beneficial and warrant further study.

WHICH ATRIAL FIBRILLATION PATIENTS NEED BRIDGING ANTICOAGULATION?

When patients receiving anticoagulation need surgery, we need to carefully assess the risks of thromboembolism without anticoagulation vs bleeding with anticoagulation.

Historically, we tended to worry more about thromboembolism24; however, recent studies have revealed a significant risk of bleeding when long-term anticoagulant therapy is bridged (ie, interrupted and replaced with a shorter-acting agent in the perioperative period), with minimal to no decrease in thromboembolic events.25–27

American College of Cardiology guideline

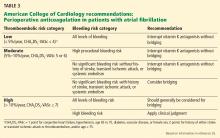

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology8 published a guideline on periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. The guideline includes a series of decision algorithms on whether and when to interrupt anticoagulation, whether and how to provide bridging anticoagulation, and how to restart postprocedural anticoagulation.

When deciding whether to interrupt anticoagulation, we need to consider the risk of bleeding posed both by patient-specific factors and by the type of surgery. Bridging anticoagulation is not indicated when direct oral anticoagulants (eg, dabigatran, apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) are interrupted for procedures.

Unlike an earlier guideline statement by the American College of Chest Physicians,24 this consensus statement emphasizes using the CHA2DS2-VASc score as a predictor of thromboembolic events rather than the CHADS2 core.

Table 3 summarizes the key points in the guidance statement about which patients should receive periprocedural bridging anticoagulation.

As evidence continues to evolve in this complicated area of perioperative medicine, it will remain important to continue to create patient management plans that take individual patient and procedural risks into account.

IS FRAILTY SCREENING BENEFICIAL BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY?

Frailty, defined as a composite score of a patient’s age and comorbidities, has great potential to become an obligatory factor in perioperative risk assessment. However, it remains difficult to incorporate frailty scoring into clinical practice due to variations among scoring systems,28 uncertain outcome data, and the imprecise role of socioeconomic factors. In particular, the effect of frailty on perioperative mortality over longer periods of time is uncertain.

McIsaac et al: Higher risk in frail patients

McIsaac and colleagues at the University of Ottawa used a frailty scoring system developed at Johns Hopkins University to evaluate the effect of frailty on all-cause postoperative mortality in approximately 202,000 patients over a 10-year period.9 Although this scoring system is proprietary, it is based on factors such as malnutrition, dementia, impaired vision, decubitus ulcers, urinary incontinence, weight loss, poverty, barriers to access of care, difficulty in walking, and falls.

After adjusting for the procedure risk, patient age, sex, and neighborhood income quintile, the 1-year mortality risk was significantly higher in the frail group (absolute risk 13.6% vs 4.8%; adjusted hazard ratio 2.23; 95% CI 2.08–2.40). The risk of death in the first 3 days was much higher in frail than in nonfrail patients (hazard ratio 35.58; 95% CI 29.78–40.1), but the hazard ratio decreased to approximately 2.4 by day 90.

The authors emphasize that the elevated risk for frail patients warrants particular perioperative planning, though it is not yet clear what frailty-specific interventions should be performed. Further study is needed into the benefit of “prehabilitation” (ie, exercise training to “build up” a patient before surgery) for perioperative risk reduction.

Hall et al: Better care for frail patients

Hall et al10 instituted a quality improvement initiative for perioperative care of patients at the Omaha Veterans Affairs Hospital. Frail patients were identified using the Risk Analysis Index, a 14-question screening tool previously developed and validated over several years using Veterans Administration databases.29 Questions in the Risk Analysis Index cover living situation, any diagnosis of cancer, ability to perform activities of daily living, and others.

To maximize compliance, a Risk Analysis Index score was required to schedule a surgery. Patients with high scores underwent further review by a designated team of physicians who initiated informal and formal consultations with anesthesiologists, critical care physicians, surgeons, and palliative care providers, with the goals of minimizing risk, clarifying patient goals or resuscitation wishes, and developing comprehensive perioperative planning.10

Approximately 9,100 patients were included in the cohort. The authors demonstrated a significant improvement in mortality for frail patients at 30, 180, and 365 days, but noted an improvement in postoperative mortality for the nonfrail patients as well, perhaps due to increased focus on geriatric patient care. In particular, the mortality rate at 365 days dropped from 34.5% to 11.7% for frail patients who underwent this intervention.

While this quality improvement initiative was unable to examine how surgical rates changed in frail patients, it is highly likely that very high-risk patients opted out of surgery or had their surgical plan change, though the authors point out that the overall surgical volume at the institution did not change significantly. As well, it remains unclear which particular interventions may have had the most effect in improving survival, as the perioperative plans were individualized and continually adjusted throughout the study period.

Nonetheless, this article highlights how higher vigilance, individualized planning and appreciation of the high risks of frail patients is associated with improved patient survival postoperatively. Although frailty screening is still in its early stages and further work is needed, it is likely that performing frailty screening in elderly patients and utilizing interdisciplinary collaboration for comprehensive management of frail patients can improve their postoperative course.