Basics of study design: Practical considerations

Using reference management software

One of the most important things you can do to make your research life easier is to use some sort of reference management software. As described in Wikipedia, “Reference management software, citation management software or personal bibliographic management software is software for scholars and authors to use for recording and using bibliographic citations (references). Once a citation has been recorded, it can be used time and again in generating bibliographies, such as lists of references in scholarly books, articles, and essays.” I was late in adopting this technology, but now I am a firm believer. Most Internet reference sources offer the ability to download citations to your reference management software. Downloading automatically places the citation into a searchable database on your computer with backup to the Internet. In addition, you can get the reference manager software to find a PDF version of the manuscript and store it with the citation on your computer (and/or in the Cloud) automatically.

But the most powerful feature of such software is its ability to add or subtract and rearrange the order of references in your manuscripts as you are writing, using seamless integration with Microsoft Word. The references can be automatically formatted using just about any journal’s style. This is a great time saver for resubmitting manuscripts to different journals. If you are still numbering references by hand (God forbid) or even using the Insert Endnote feature in Word (deficient when using multiple occurrences of the same reference), your life will be much easier if you take the time to start using reference management software.

The most popular commercial software is probably EndNote (endnote.com). A really good free software system with about the same functionality as Zotero (zotero.com). Search for “comparison of reference management software” in Wikipedia. You can find tutorials on software packages in YouTube.

STUDY DESIGN

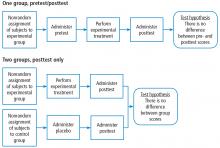

When designing the experiment, note that there are many different approaches, each with their advantages and disadvantages. A full treatment of this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that pre-experimental designs (Figure 2) are considered to generate weak evidence. But they are quick and easy and might be appropriate for pilot studies.

Quasi-experimental designs (Figure 3) generate a higher level of evidence. Such a design might be appropriate when you are stuck with collecting a convenience sample, rather than being able to use a full randomized assignment of study subjects.

The fully randomized design (Figure 4) generates the highest level of evidence. This is because if the sample size is large enough, the unknown and uncontrollable sources of bias are evenly distributed between the study groups.

BASIC MEASUREMENT METHODS

If your research involves physical measurements, you need to be familiar with the devices considered to be the gold standards. In cardiopulmonary research, most measurements involve pressure volume, flow, and gas concentration. You need to know which devices are appropriate for static vs dynamic measurements of these variables. In addition, you need to understand issues related to systematic and random measurement errors and how these errors are managed through calibration and calibration verification. I recommend these two textbooks:

Principles and Practice of Intensive Care Monitoring 1st Edition by Martin J. Tobin MD.

- This book is out of print, but if you can find a used copy or one in a library, it describes just about every kind of physiologic measurement used in clinical medicine.

Medical Instrumentation: Application and Design 4th Edition by John G. Webster.

- This book is readily available and reasonably priced. It is a more technical book describing medical instrumentation and measurement principles. It is a standard textbook for biometrical engineers.

STATISTICS FOR THE UNINTERESTED

I know what you are thinking: I hate statistics. Look at the book Essential Biostatistics: A Nonmathematical Approach.15 It is a short, inexpensive paperback book that is easy to read. The author does a great job of explaining why we use statistics rather than getting bogged down explaining how we calculate them. After all, novice researchers usually seek the help of a professional statistician to do the heavy lifting.

My book, Handbook for Health Care Research,16 covers most of the statistical procedures you will encounter in medical research and gives examples of how to use a popular tactical software package called SigmaPlot. By the way, I strongly suggest that you consult a statistician early in your study design phase to avoid the disappointment of finding out later that your results are uninterpretable. For an in-depth treatment of the subject, I recommend How to Report Statistics in Medicine.17

Statistical bare essentials

To do research or even just to understand published research reports, you must have at least a minimal skill set. The necessary skills include understanding some basic terminology, if only to be able to communicate with a statistician consultant. Important terms include levels of measurement (nominal, ordinal, continuous), accuracy, precision, measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode), measures of variability (variance, standard deviation, coefficient of variation), and percentile. The first step in analyzing your results is usually to represent it graphically. That means you should be able to use a spreadsheet to make simple graphs (Figure 5).

You should also know the basics of inferential statistics (ie, hypothesis testing). For example, you need to know the difference between parametric and non-parametric tests. You should be able to explain correlation and regression and know when to use Chi-squared vs a Fisher exact test. You should know that when comparing two mean values, you typically use the Student’s t test (and know when to use paired vs unpaired versions of the test). When comparing more than 2 mean values, you use analysis of variance methods (ANOVA). You can teach yourself these concepts from a book,16 but even an introductory college level course on statistics will be immensely helpful. Most statistics textbooks provide some sort of map to guide your selection of the appropriate statistical test (Figure 6), and there are good articles in medical journals.

You can learn a lot simply by reading the Methods section of research articles. Authors will often describe the statistical tests used and why they were used. But be aware that a certain percentage of papers get published with the wrong statistics.18

One of the underlying assumptions of most parametric statistical methods is that the data may be adequately described by a normal or Gaussian distribution. This assumption needs to be verified before selecting a statistical test. The common test for data normality is the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The following text from a methods section describes 2 very common procedures—the Student’s t test for comparing 2 mean values and the one-way ANOVA for comparing more than 2 mean values.19

“Normal distribution of data was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Body weights between groups were compared using one-way ANOVA for repeated measures to investigate temporal differences. At each time point, all data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA to compare PCV and VCV groups. Tukey’s post hoc analyses were performed when significant time effects were detected within groups, and Student’s t test was used to investigate differences between groups. Data were analyzed using commercial software and values were presented as mean ± SD. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.”