Necrotizing pancreatitis: Diagnose, treat, consult

ABSTRACT

Necrosis significantly increases rates of morbidity and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Hospitalists and general internists are on the front lines in identifying severe cases and consulting the appropriate specialists for optimal multidisciplinary care.

KEY POINTS

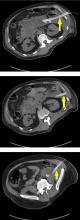

- Selective and appropriate timing of radiologic imaging is vital in managing necrotizing pancreatitis. Protocols are valuable tools.

- While the primary indication for debridement and drainage in necrotizing pancreatitis is infection, other indications are symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis, intractable abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, and failure to thrive.

- Open surgical necrosectomy remains an important treatment for infected pancreatic necrosis or intractable symptoms.

- A “step-up” approach starting with a minimally invasive procedure and escalating if the initial intervention is unsuccessful is gradually becoming the standard of care.

ROLE OF INTERVENTION

The treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis has changed rapidly, thanks to a growing experience with minimally invasive techniques.

Indications for intervention

Infected pancreatic necrosis is the primary indication for surgical, percutaneous, or endoscopic intervention.

In sterile necrosis, the threshold for intervention is less clear, and intervention is often reserved for patients who fail to clinically improve or who have intractable abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, or fistulating disease.26

In asymptomatic cases, intervention is almost never indicated regardless of the location or size of the necrotic area.

In walled-off pancreatic necrosis, less-invasive and less-morbid interventions such as endoscopic or percutaneous drainage or video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement can be done.

Timing of intervention

In the past, delaying intervention was thought to increase the risk of death. However, multiple studies have found that outcomes are often worse if intervention is done early, likely due to the lack of a fully formed fibrous wall or demarcation of the necrotic area.27

If the patient remains clinically stable, it is best to delay intervention until at least 4 weeks after the index event to achieve optimal outcomes. Delay can often be achieved by antibiotic treatment to suppress bacteremia and endoscopic or percutaneous drainage of infected collections to control sepsis.

Open surgery

The gold-standard intervention for infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis is open necrosectomy. This involves exploratory laparotomy with blunt debridement of all visible necrotic pancreatic tissue.

Methods to facilitate later evacuation of residual infected fluid and debris vary widely. Multiple large-caliber drains can be placed to facilitate irrigation and drainage before closure of the abdominal fascia. As infected pancreatic necrosis carries the risk of contaminating the peritoneal cavity, the skin is often left open to heal by secondary intention. An interventional radiologist is frequently enlisted to place, exchange, or downsize drainage catheters.

Infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis often requires more than one operation to achieve satisfactory debridement.

The goals of open necrosectomy are to remove nonviable tissue and infection, preserve viable pancreatic tissue, eliminate fistulous connections, and minimize damage to local organs and vasculature.

Minimally invasive techniques

Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement has been described as a hybrid between endoscopic and open retroperitoneal debridement.28 This technique requires first placing a percutaneous catheter into the necrotic area through the left flank to create a retroperitoneal tract. A 5-cm incision is made and the necrotic space is entered using the drain for guidance. Necrotic tissue is carefully debrided under direct vision using a combination of forceps, irrigation, and suction. A laparoscopic port can also be introduced into the incision when the procedure can no longer be continued under direct vision.29,30

Although not all patients are candidates for minimal-access surgery, it remains an evolving surgical option.

Endoscopic transmural debridement is another option for infected pancreatic necrosis and symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Depending on the location of the necrotic area, an echoendoscope is passed to either the stomach or duodenum. Guided by endoscopic ultrasonography, a needle is passed into the collection, allowing subsequent fistula creation and stenting for internal drainage or debridement. In the past, this process required several steps, multiple devices, fluoroscopic guidance, and considerable time. But newer endoscopic lumen-apposing metal stents have been developed that can be placed in a single step without fluoroscopy. A slimmer endoscope can then be introduced into the necrotic cavity via the stent, and the necrotic debris can be debrided with endoscopic baskets, snares, forceps, and irrigation.9,31

Similar to surgical necrosectomy, satisfactory debridement is not often obtained with a single procedure; 2 to 5 endoscopic procedures may be needed to achieve resolution. However, the luminal approach in endoscopic necrosectomy avoids the significant morbidity of major abdominal surgery and the potential for pancreaticocutaneous fistulae that may occur with drains.

In a randomized trial comparing endoscopic necrosectomy vs surgical necrosectomy (video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement and exploratory laparotomy),32 endoscopic necrosectomy showed less inflammatory response than surgical necrosectomy and had a lower risk of new-onset organ failure, bleeding, fistula formation, and death.32

Selecting the best intervention for the individual patient

Given the multiple available techniques, selecting the best intervention for individual patients can be challenging. A team approach with input from a gastroenterologist, surgeon, and interventional radiologist is best when determining which technique would best suit each patient.

Surgical necrosectomy is still the treatment of choice for unstable patients with infected pancreatic necrosis or multiple, inaccessible collections, but current evidence suggests a different approach in stable infected pancreatic necrosis and symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

The Dutch Pancreatitis Group28 randomized 88 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis to open necrosectomy or a minimally invasive “step-up” approach consisting of up to 2 percutaneous drainage or endoscopic debridement procedures before escalation to video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement. The step-up approach resulted in lower rates of morbidity and death than surgical necrosectomy as first-line treatment. Furthermore, some patients in the step-up group avoided the need for surgery entirely.30