Optimizing diagnostic testing for venous thromboembolism

ABSTRACT

Diagnostic algorithms for venous thromboembolism exist, but most do not provide detailed guidance as to which patients, if any, may benefit from screening for thrombophilia. This article provides an overview of the optimized diagnosis of venous thromboembolism, with a focus on the appropriate use of thrombophilia screening.

KEY POINTS

- A pretest clinical prediction tool such as the Wells score can help in deciding whether a patient with suspected venous thromboembolism warrants further workup.

- A clinical prediction tool should be used in concert with additional laboratory testing (eg, D-dimer) and imaging in patients at risk.

- In many cases, screening for thrombophilia to determine the cause of a venous thromboembolic event may be unwarranted.

- Testing for thrombophilia should be based on whether a venous thromboembolic event was provoked or unprovoked.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS FOR PULMONARY EMBOLISM

Computed tomography

Imaging is warranted in patients who have a high pretest probability of pulmonary embolism, or in whom the D-dimer assay was positive but the pretest probability was low or moderate.

Once the gold standard, pulmonary angiography is no longer recommended for the initial diagnosis of pulmonary embolism because it is invasive, often unavailable, less sophisticated, and more expensive than noninvasive imaging techniques such as CT angiography. It is still used, however, in catheter-directed thrombolysis.

Thus, multiphasic CT angiography, as guided by pretest probability and the D-dimer level, is the imaging test of choice in the evaluation of pulmonary embolism. It can also offer insight into thrombotic burden and can reveal concurrent or alternative diagnoses (eg, pneumonia).

Ventilation-perfusion scanning

When CT angiography is unavailable or the patient should not be exposed to contrast medium (eg, due to concern for contrast-induced nephropathy or contrast allergy), ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scanning remains an option for ruling out pulmonary embolism.22

Anderson et al23 compared CT angiography and V/Q scanning in a study in 1,417 patients considered likely to have acute pulmonary embolism. Rates of symptomatic pulmonary embolism during 3-month follow-up were similar in patients who initially had negative results on V/Q scanning compared with those who initially had negative results on CT angiography. However, this study used single-detector CT scanners for one-third of the patients. Therefore, the results may have been different if current technology had been used.

Limitations of V/Q scanning include length of time to perform (30–45 minutes), cost, inability to identify other causes of symptoms, and difficulty with interpretation when other pulmonary pathology is present (eg, lung infiltrate). V/Q scanning is helpful when negative but is often reported based on probability (low, intermediate, or high) and may not provide adequate guidance. Therefore, CT angiography should be used whenever possible for diagnosing pulmonary embolism.

Other tests for pulmonary embolism

Electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography, and chest radiography may aid in the search for alternative diagnoses and assess the degree of right heart strain as a sequela of pulmonary embolism, but they do not confirm the diagnosis.

ORDER IMAGING ONLY IF NEEDED

Diagnostic imaging can be optimized by avoiding unnecessary tests that carry both costs and clinical risks.

Most patients in whom acute pulmonary embolism is discovered will not need testing for deep vein thrombosis, as they will receive anticoagulation regardless. Similarly, many patients with acute symptomatic deep vein thrombosis do not need testing for pulmonary embolism with chest CT imaging, as they too will receive anticoagulation regardless.

Therefore, clinicians are encouraged to use diagnostic reasoning while practicing high-value care (including estimating pretest probability and measuring D-dimer when appropriate), ordering additional tests judiciously and only if indicated.

THROMBOEMBOLISM IS CONFIRMED—IS FURTHER TESTING WARRANTED?

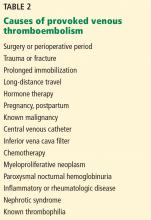

Once acute venous thromboembolism is confirmed, key considerations include whether the event was provoked or unprovoked (ie, idiopathic) and whether the patient needs indefinite anticoagulation (eg, after 2 or more unprovoked events).

Was the event provoked or unprovoked?

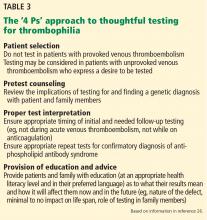

Even in cases of unprovoked venous thromboembolism, no clear consensus exists as to which patients should be tested for thrombophilia. Experts do advocate, however, that it be done only in highly selected patients and that it be coordinated with the patient, family members, and an expert in this testing. Patients for whom further testing may be considered include those with venous thromboembolism in unusual sites (eg, the cavernous sinus), with warfarin-induced skin necrosis, or with recurrent pregnancy loss.

While screening for malignancy may seem prudent in the case of unexplained venous thromboembolism, the use of CT imaging for this purpose has been found to be of low yield. In one study,24 it was not found to detect additional neoplasms, and it can lead to additional cost and no added benefit for patients.

The American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign strongly recommends consultation with an expert in thrombophilia (eg, a hematologist) before testing.25 Ordering multiple tests in bundles (hypercoagulability panels) is unlikely to alter management, could have a negative clinical impact on patients, and is generally not recommended.

The ‘4 Ps’ approach to testing

- Patient selection

- Pretest counseling

- Proper laboratory interpretation

- Provision of education and advice.

Importantly, testing should be reserved for patients in whom the pretest probability of the thrombophilic disease is moderate to high, such as testing for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or recurrent miscarriage.

Venous thromboembolism in a patient who is known to have a malignant disease does not typically warrant further thrombophilia testing, as the event was likely a sequela of the malignancy. The evaluation and management of venous thromboembolism with concurrent neoplasm is covered elsewhere.21