Chronic constipation: Update on management

ABSTRACT

Managing chronic constipation involves identifying and treating secondary causes, instituting lifestyle changes, prescribing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies, and, occasionally, referring for surgery. Several new drugs have been approved, and others are in the pipeline.

KEY POINTS

- Although newer drugs are available, lifestyle modifications and laxatives continue to be the treatments of choice for chronic constipation, as they have high response rates and few adverse effects and are relatively affordable.

- Chronic constipation requires different management approaches depending on whether colonic transit time is normal or prolonged and whether outlet function is abnormal.

- Surgical treatments for constipation are reserved for patients whose symptoms persist despite maximal medical therapy.

Outlet dysfunction

Outlet dysfunction, also called pelvic floor dysfunction or defecatory disorder, is associated with incomplete rectal evacuation. It can be a consequence of weak rectal expulsion forces (slow colonic transit, rectal hyposensitivity), functional resistance to rectal evacuation (high anal resting pressure, anismus, incomplete relaxation of the anal sphincter, dyssynergic defecation), or structural outlet obstruction (excessive perineal descent, rectoceles, rectal intussusception). About 50% of patients with outlet dysfunction have concurrent slow-transit constipation.

Dyssynergic defecation is the most common outlet dysfunction disorder, accounting for about half of the cases referred to tertiary centers. It is defined as a paradoxical elevation in anal sphincter tone or less than 20% relaxation of the resting anal sphincter pressure with weak abdominal and pelvic propulsive forces.11 Anorectal biofeedback is a therapeutic option for dyssynergic defecation, as we discuss later in this article.

SECONDARY CONSTIPATION

Constipation can be secondary to several conditions and factors (Table 1), including:

- Neurologic disorders that affect gastrointestinal motility (eg, Hirschsprung disease, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, stroke, spinal or ganglionic tumor, hypothyroidism, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, hypercalcemia)

- Drugs used to treat neurologic disorders

- Mechanical obstruction

- Diet (eg, low fiber, decreased fluid intake).

EVALUATION OF CONSTIPATION

It is crucial for physicians to efficiently use the available diagnostic tools for constipation to tailor the treatment to the patient.

Evaluation of chronic constipation begins with a thorough history and physical examination to rule out secondary constipation (Figure 1). Red flags such as unintentional weight loss, blood in the stool, rectal pain, fever, and iron-deficiency anemia should prompt referral for colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy, colitis, or other potential colonic abnormalities.12

A detailed perineal and rectal examination can help diagnose defecatory disorders and should include evaluation of the resting anal tone and the sphincter during simulated evacuation.

Laboratory tests of thyroid function, electrolytes, and a complete blood cell count should be ordered if clinically indicated.13

Further tests

Further diagnostic tests can be considered if symptoms persist despite conservative treatment or if a defecatory disorder is suspected. These include anorectal manometry, colonic transit studies, defecography, and colonic manometry.

Anorectal manometry and the rectal balloon expulsion test are usually done first because of their high sensitivity (88%) and specificity (89%) for defecatory disorders.14 These tests measure the function of the internal and external anal sphincters at rest and with straining and assess rectal sensitivity and compliance. Anorectal manometry is also used in biofeedback therapy in patients with dyssynergic defecation.15

Colonic transit time can be measured if anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are normal. The study uses radiopaque markers, radioisotopes, or wireless motility capsules to confirm slow-transit constipation and to identify areas of delayed transit in the colon.16

Defecography is usually the next step in diagnosis if anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion tests are inconclusive or if an anatomic abnormality of the pelvic floor is suspected. It can be done with a variety of techniques. Barium defecography can identify anatomic defects, scintigraphy can quantify evacuation of artificial stools, and magnetic resonance defecography visualizes anatomic landmarks to assess pelvic floor motion without exposing the patient to radiation.17,18

Colonic manometry is most useful in patients with refractory slow-transit constipation and can identify patients with isolated colonic motor dysfunction with no pelvic floor dysfunction who may benefit from subtotal colectomy and end-ileostomy.7

TRADITIONAL TREATMENTS STILL THE MAINSTAY

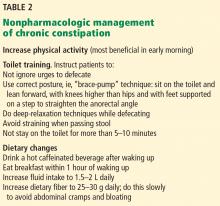

Nonpharmacologic treatments are the first-line options for patients with normal-transit and slow-transit constipation and should precede diagnostic testing. Lifestyle modifications and dietary changes (Table 2) aim to augment the known factors that stimulate the gastrocolic reflex and increase intestinal motility by high-amplitude propagated contractions.

Increasing physical activity increases intestinal gas clearance, decreases bloating, and lessens constipation.19,20

Toilet training is an integral part of lifestyle modifications.21

Diet. Drinking hot caffeinated beverages, eating breakfast within an hour of waking up, and consuming fiber in the morning (25–30 g of fiber daily) have traditionally been recommended as the first-line measures for chronic constipation. Dehydrated patients with constipation also benefit from increasing their fluid intake.22

LAXATIVES

Fiber (bulk-forming laxatives) for normal-transit constipation

Fiber remains a key part of the initial management of chronic constipation, as it is cheap, available, and safe. Increasing fiber intake is effective for normal-transit constipation, but patients with slow-transit constipation or refractory outlet dysfunction are less likely to benefit.23 Other laxatives are incorporated into the regimen if first-line nonpharmacologic interventions fail (Table 3).

Bulk-forming laxatives include insoluble fiber (wheat bran) and soluble fiber (psyllium, methylcellulose, inulin, calcium polycarbophil). Insoluble fiber, though often used, has little impact on symptoms of chronic constipation after 1 month of use, and up to 60% of patients report adverse effects from it.24 On the other hand, clinical trials have shown that soluble fiber such as psyllium facilitates defecation and improves functional bowel symptoms in patients with normal-transit constipation.25

Patients should be instructed to increase their dietary fiber intake gradually to avoid adverse effects and should be told to expect significant symptomatic improvement only after a few weeks. They should also be informed that increasing dietary fiber intake can cause bloating but that the bloating is temporary. If it continues, a different fiber can be tried.

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives are often employed as a first- line laxative treatment option for patients with constipation. They draw water into the lumen by osmosis, helping to soften stool and speed intestinal transit. They include macrogols (inert polymers of ethylene glycol), nonabsorbable carbohydrates (lactulose, sorbitol), magnesium products, and sodium phosphate products.

Polyethylene glycol, the most studied osmotic laxative, has been shown to maintain therapeutic efficacy for up to 2 years, though it is not generally used this long.26 A meta-analysis of 10 randomized clinical trials found it to be superior to lactulose in improving stool consistency and frequency, and rates of adverse effects were similar to those with placebo.27

Lactulose and sorbitol are semisynthetic disaccharides that are not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Apart from the osmotic effect of the disaccharide, these sugars are metabolized by colonic bacteria to acetic acid and other short-chain fatty acids, resulting in acidification of the stool, which exerts an osmotic effect in the colonic lumen.

Lactulose and sorbitol were shown to have similar efficacy in increasing the frequency of bowel movements in a small study, though patients taking lactulose had a higher rate of nausea.28

The usual recommended dose is 15 to 30 mL once or twice daily.

Adverse effects include gas, bloating, and abdominal distention (due to fermentation by colonic bacteria) and can limit long-term use.

Magnesium citrate and magnesium hydroxide are strong osmotic laxatives, but so far no clinical trial has been done to assess their efficacy in constipation. Although the risk of hypermagnesemia is low with magnesium-based products, this group of laxatives is generally avoided in patients with renal or cardiac disease.29

Sodium phosphate enemas (Fleet enemas) are used for bowel cleansing before certain procedures but have only limited use in constipation because of potential adverse effects such as hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and the rarer but more serious complication of acute phosphate nephropathy.30

Stimulant laxatives for short-term use only

Stimulant laxatives include glycerin, bisacodyl, senna, and sodium picosulfate. Sodium piosulfate and bisacodyl have been validated for treatment of chronic constipation for up to 4 weeks.31–33

Stimulant laxative suppositories should be used 30 minutes after meals to augment the physiologic gastrocolic reflex.

As more evidence is available for osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol, they tend to be preferred over stimulant agents, especially for long-term use. Clinicians have traditionally hesitated to prescribe stimulant laxatives for long-term use, as they were thought to damage the enteric nervous system.34 Although more recent studies have not shown this potential effect,35 more research is warranted on the use of stimulant laxatives for longer than 4 weeks.