Iodine deficiency: Clinical implications

ABSTRACT

Iodine is crucial for thyroid hormone synthesis and fetal neurodevelopment. Major dietary sources of iodine in the United States are dairy products and iodized salt. Potential consequences of iodine deficiency are goiter, hypothyroidism, cretinism, and impaired cognitive development. Although iodine status in the United States is considered sufficient at the population level, intake varies widely across the population, and the percentage of women of childbearing age with iodine deficiency is increasing. Physicians should be aware of the risks of iodine deficiency and the indications for iodine supplementation, especially in women who are pregnant or lactating.

KEY POINTS

- Adequate iodine intake during pregnancy is critical for normal fetal development.

- Major sources of dietary iodine in the United States are dairy products and iodized salt.

- The daily iodine requirement for nonpregnant adults is 150 µg, and for pregnant women it is 220 to 250 μg. Pregnant and lactating women should take a daily iodine supplement to ensure adequate iodine intake.

- Assessing the risk of iodine deficiency from clinical signs and from the history is key to diagnosing iodine deficiency. Individual urine iodine concentrations may vary from day to day. Repeated samples can be used to confirm iodine deficiency.

Thyroglobulin

Thyroglobulin is a thyroid-specific protein involved in the synthesis of thyroid hormone. Small amounts can be detected in the blood of healthy people. In the absence of thyroid damage, the amount of serum thyroglobulin depends on thyroid cell mass and TSH stimulation. The serum level is elevated in iodine deficiency as a result of chronic TSH stimulation and thyroid hyperplasia. Thus, thyroglobulin can serve as a marker of iodine deficiency.

Serum thyroglobulin assays have been adapted for use on dried whole-blood spots, which require only a few drops of whole blood collected on filter paper and left to air-dry. The results of the dried whole-blood assay correlate closely with those of the serum assay.31 An established international dried whole-blood thyroglobulin reference range for iodine-sufficient school-age children is 4 to 40 μg/L.32 A median level of less than 13 μg/L in school-age children indicates iodine sufficiency in the population.33

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

Iodine deficiency lowers serum T4, which in turn leads to increased serum TSH. Therefore, iodine-deficient populations generally have higher TSH than iodine-sufficient groups. However, the TSH values in older children and adults with iodine deficiency are not significantly different from values of those with adequate iodine intake. Therefore, TSH is not a practical marker of iodine deficiency in the general population.

,In contrast, TSH in newborns is a reasonable indicator of population iodine status. The newborn thyroid has limited iodine stores compared with that of an adult and hence a much higher iodine turnover rate. TSH from the cord blood is markedly elevated in newborns of mothers with moderate to severe iodine deficiency.34 A high prevalence of newborns with elevated TSH should therefore reflect iodine deficiency in the area where the mothers of the newborns live.

TSH is now routinely checked in newborns to screen for congenital hypothyroidism. TSH is typically checked 2 to 5 days after delivery to avoid confusion with transient physiologic TSH elevation, which occurs within a few hours after birth and decreases rapidly in 24 hours. The WHO has proposed that a more than 3% prevalence of newborns with TSH values higher than 5 mU/L from blood samples collected 3 to 4 days after birth indicates iodine deficiency in a population.1 This threshold appears to correlate well with the iodine status of the population defined by the WHO’s median urinary iodine concentration.35,36

But several other factors can influence the measurement of newborn TSH, such as prematurity, time of blood collection, maternal or newborn exposure to iodine-containing antiseptics, and the TSH assay methodology. These potential confounding factors limit the role of neonatal TSH as a reliable monitoring tool for iodine deficiency.35,37

Thyroid size

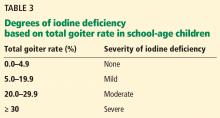

The size of the thyroid gland varies inversely with iodine intake. Thyroid size can be assessed by either palpation or ultrasonography, with the latter being more sensitive. The goiter rate in school-age children can be used to determine the severity of iodine deficiency in the population (Table 3). A goiter rate of 5% or more in school-age children suggests the presence of iodine deficiency in the community.

Although thyroid size is easy to estimate by palpation, it has low sensitivity and specificity to detect iodine deficiency and high interobserver variation. Thyroid ultrasonography provides a more precise measurement of thyroid gland volume. Zimmermann et al38 provided reference data on thyroid volume stratified by age, sex, and body surface area of school-age children in iodine-sufficient areas.38 Results of ultrasonography in a population is then compared with these reference data. The higher the percentage of the population with thyroid volume exceeding the 97th percentile of the reference range, the more severe the iodine deficiency. However, the WHO does not specify how to grade the degree of iodine deficiency based on the thyroid volume obtained with ultrasonography. Follow-up studies showed no significant correlation between urinary iodine concentration and thyroid size.39,40

Thyroid size decreases slowly after iodine repletion. Therefore, the goiter rate may remain high for several years after iodine supplementation begins.1,9

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

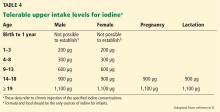

Treatment of iodine deficiency should be instituted at the levels recommended by the Institute of Medicine and the WHO. The tolerable upper intake levels for iodine are outlined in Table 4. In a nonpregnant adult, 150 μg/day is sufficient for normal thyroid function. Iodine intake should be higher for pregnant and lactating women (250 μg/day according to the WHO recommendation).

Iodine supplementation is easily achieved by using iodized salt or an iodine-containing daily multivitamin.

In patients with overt hypothyroidism from iodine deficiency, we recommend initiating levothyroxine treatment along with iodine supplementation to restore euthyroidism, with consideration of possible interruption in 6 to 12 months when the urine iodine has normalized and goiter size has decreased. Thyroid function should be reassessed 4 to 6 weeks after discontinuation of levothyroxine.

At the population level, iodine deficiency can usually be prevented by iodization of food products or the water supply. In developing countries where salt iodization is not practical, iodine deficiency has been eradicated by adding iodine drops to well water or by injecting people with iodized oil.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Iodine is essential for thyroid hormone synthesis. It can be obtained by eating iodine-containing foods or by using iodized salt. The WHO classifies iodine deficiency based on the median urinary iodine concentration. Iodine nutrition at the community level is best assessed by measurements of urinary iodine, thyroglobulin, serum TSH, and thyroid size.

Adequate iodine intake during pregnancy is important for fetal development. Iodine deficiency is associated with goiter and hypothyroidism. Severe iodine deficiency during pregnancy is associated with cretinism.

There is evidence that mild to moderate iodine deficiency can cause impaired cognitive development and that correcting the iodine deficiency can significantly improve cognitive function.

CASE FOLLOW-UP

This patient had been following a strict vegan diet with very little intake of iodized salt. Her dietary history and the presence of goiter suggested iodine deficiency. She was instructed to take an iodine supplement 150 μg/day to meet her daily requirement. After 2 months of iodine supplementation, her urine iodine concentration had increased to 58 μg/L. She remained biochemically euthyroid.