Distress Screening and Management in an Outpatient VA Cancer Clinic: A Pilot Project Involving Ambulatory Patients Across the Disease Trajectory

A plan-do-act model of quality improvement (QI) was used to support the development and implementation of the distress-screening process. At the beginning of the project, the institutional review board (IRB) reviewed the protocol and determined that informed consent was not necessary because a QI project for a new standard of care did not require IRB approval. The CoE team met for about 4 months to develop a policy and procedure for the process, based on evidence from national guidelines, a review of the literature, and a discussion of the benefits and burdens of implementation within the current practice.

Limiting initial implementation to a single clinic day made the process more manageable. Descriptive methods analyzed the incidence and percentage of overall distress in this veteran population and quantified the incidences and percentages of each DT component. Feedback from patients and staff offered information on the feasibility of and satisfaction with the process.

From May 2012 to May 2014, all patients who attended the Monday outpatient CoE clinic with a diagnosis of cancer or a cancer concern were given the NCCN, 2.2013 DT instrument by the registration desk clerk at the time they registered for their clinic appointment. 16 Veterans who had difficulty filling out the DT or who had diminished capacity were assisted in completing the instrument by a designated family member and/or the clinic RN.

The completed instrument was evaluated by the CNS patient navigator, and any patient with a score ≥ 4 received an automatic referral to the behavioral health psychologist, social worker, NP, or all team members and their trainees, depending on the areas of distress (eg, practical, family, and emotional problems, spiritual/religious concerns, and/or physical problems) endorsed by the patient.

A psychiatrist was not embedded into the team but worked closely with the team’s oncology psychologist. The psychologist communicated directly with the psychiatrist, and the plan was shared with the team through the electronic medical record (EMR). The appropriate team member(s) and trainee(s) saw the patient at the visit to address needs in real time. Access to palliative care support and spiritual care was readily available if needed.

Distress screenings were recorded in a templated note in the patient’s EMR, which allowed the team to follow the distress scores on an individual basis across the cancer disease trajectory and to assess response to interventions. Multiple screenings of individuals resulted from the fact that many of the patients were seen monthly or every 3/6/9 months, depending on their disease and treatment status. Because levels of distress can fluctuate, distress was assessed at every visit to determine whether an intervention was needed at that visit. Once distress screenings were recorded in the patient’s EMR, the DT instrument was de-identified and given to the CoE research consultant to enter into a database file for analysis.

Trainees were educated about the use of the DT at time of diagnosis and across the disease trajectory. The 4-week CoE curriculum included 2 weeks of conference time to teach about the roles of psychologist, oncology social worker, and survivorship NP in assessing and initiating interventions to address the multidimensional components of the DT. Trainees working with a veteran who was distressed participated in the assessment(s) and intervention(s) for all components of distress that were endorsed.

Results

A total of 866 distress screenings were performed during the first 2 years of the project. Since all patients were screened at all visits, the 866 distress screenings reflect multiple screenings for 445 unique patients. Of the 866 screenings, 290 (33%) had distress scores of ≥ 4, meeting the criteria for intervention. Screenings reflected patient visits at any point in the disease trajectory. Because this was a new standard of care QI project rather than a research project, additional data, such as diagnosis or staging, were not collected, and IRB approval was not needed.

Because the NCCN Guideline recommendation for intervention is a score of ≥ 4, the descriptive statistics focused on those with moderate-to-severe distress. However, there were numerous occasions when the veteran would report a score of 0 to 3 and still endorse a number of the problems on the DT. The CNS and RN on the team discussed these findings with the appropriate discipline. For example, if the veteran reported a score of 1 but endorsed all 6 components on the emotional problem list, the nurses discussed the patient with the social worker or psychologist to determine whether behavioral health intervention was needed.

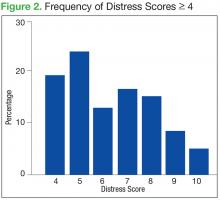

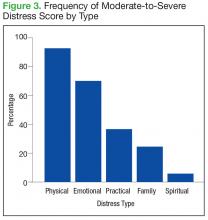

The mean distress score for the 290 screenings ≥ 4 was 6.3 on a 0 to 10 scale; median was 6.0 and mode 5.0. Two hundred ten of these screenings (72%) were categorized as moderate distress (4-7), and 80 patients (28%) reported severe distress (Figure 2). If the veteran left a box empty on the problem list, itwas recorded as missing. The frequency that patients reported each type of distress are reported in Figure 3.

The incidence of each component of distress, from those screenings with a score of ≥ 4 is described below, along with case study examples for each component. Team members involved in patient interventions provided these case studies to demonstrate clinical examples of the veteran’s distress from the problem list on the DT.

Practical/Family Distress

Practical issues were reported in 38% of the screenings (109/290). Intervention for moderate-to-severe distress associated with practical problems and family issues was provided by the team social worker. The social worker frequently addressed transportationrelated distress. Providing transportation was essential for adherence to clinic appointments, follow-up testing, treatments, and ultimately, disease management. Housing was also a problem for many veterans. It is critical that patients have access to electricity, heating, food, and water to be able to safely undergo adjuvant therapy. Thus, treatments decisions could be impacted by the veterans’ housing and transportation issues; immediate access to social work support is essential for quality cancer care.

Twenty-six percent of patients that were screened expressed concerns with practical and/or family problems (75/289). Issues of domestic violence, difficulties dealing with a significant other, and concerns about children were referred to social work (Table 1).

Case Study

Ms. S. is a veteran aged 71 years with recently diagnosed breast cancer. She is being seen in the clinic for a postoperative visit following partial mastectomy and is anticipating beginning radiation therapy within the next 3 weeks. She reports a distress score of 7 and identifies concerns about work and transportation to the clinic as the sources of distress. The social worker meets with the patient and learns that she fears losing her job because of the daily travel time to and from radiation and that she cannot afford to travel 65 miles daily to LSCVAMC for radiation. The social worker listens to her concerns and assists her with a plan for short-term disability and VA housing during her radiation therapy treatments. Ms. S. was able to complete radiation at LSCVAMC with temporary housing and to return to work after therapy.

Emotional Distress

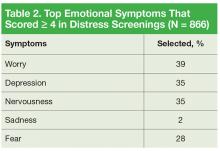

Patients who identified that their moderate-to-severe distress was related to emotional problems received same-day intervention from a psychologist skilled in providing emotional support, cognitive behavioral strategies, and assessing the need for referral to either a psychiatrist or oncology social worker. Seventy-one percent of patients reported emotional problems, such as worry, depression, and nervousness (Table 2).

Case Study

Mr. K. is a veteran aged 71 years with a new diagnosis of breast cancer. He lives on his own but has family and a few friends nearby. He reports that he doesn’t like to share his problems with others and has not told anyone of his new diagnosis. Mr. K. rates his distress a 7 and endorses worry, fear, and depression. At a treatment-planning visit, he agrees to see the psychologist for help in dealing with his distress. Treatment involves a mastectomy followed by hormonal therapy.