Burnout in inpatient‐based versus outpatient‐based physicians: A systematic review and meta‐analysis

BACKGROUND

Burnout is a syndrome affecting the entirety of work life and characterized by cynicism, detachment, and inefficacy. Despite longstanding concerns about burnout in hospital medicine, few data about burnout in hospitalists have been published.

PURPOSE

A systematic review of the literature on burnout in inpatient‐based and outpatient‐based physicians worldwide was undertaken to determine whether inpatient physicians experience more burnout than outpatient physicians.

DATA SOURCES

Five medical databases were searched for relevant terms with no language restrictions. Authors were contacted for unpublished data and clarification of the practice location of study subjects.

STUDY SELECTION

Two investigators independently reviewed each article. Included studies provided a measure of burnout in inpatient and/or outpatient nontrainee physicians.

DATA EXTRACTION

Fifty‐four studies met inclusion criteria, 15 of which provided direct comparisons of inpatient and outpatient physicians. Twenty‐eight studies used the same burnout measure and therefore were amenable to statistical analysis.

DATA SYNTHESIS

Outpatient physicians reported more emotional exhaustion than inpatient physicians. No statistically significant differences in depersonalization or personal accomplishment were found. Further comparisons were limited by the heterogeneity of instruments used to measure burnout and the lack of available information about practice location in many studies.

CONCLUSIONS

The existing literature does not support the widely held belief that burnout is more frequent in hospitalists than outpatient physicians. Better comparative studies of hospitalist burnout are needed. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2013;8:653–664. © 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospital medicine is a rapidly growing field of US clinical practice.[1] Almost since its advent, concerns have been expressed about the potential for hospitalists to burn out.[2] Hospitalists are not unique in this; similar concerns heralded the arrival of other location‐defined specialties, including emergency medicine[3] and the full‐time intensivist model,[4] a fact that has not gone unnoted in the literature about hospitalists.[5] The existing international literature on physician burnout provides good reason for this concern. Inpatient‐based physicians tend to work unpredictable schedules, with substantial impact on home life.[6] They tend to be young, and much burnout literature suggests a higher risk among younger, less‐experienced physicians.[7] When surveyed, hospitalists have expressed more concerns about their potential for burnout than their outpatient‐based colleagues.[8] In fact, data suggesting a correlation between inpatient practice and burnout predate the advent of the US hospitalist movement. Increased hospital time was reported to correlate with higher rates of burnout in internists,[9] family practitioners,[10] palliative physicians,[11] junior doctors,[12] radiologists,[13] and cystic fibrosis caregivers.[14] In 1987, Keinan and Melamed[15] noted, Hospital work by its very nature, as compared to the work of a general practitioner, deals with the more severe and complicated illnesses, coupled with continuous daily contacts with patients and their anxious families. In addition, these physicians may find themselves embroiled in the power struggles and competition so common in their work environment.

There are other features, however, that may protect inpatient physicians from burnout. Hospital practice can facilitate favorable social relations involving colleagues, co‐workers, and patients,[16] a factor that may be protective.[17] A hospitalist schedule also can allow more focused time for continuing medical education, research, and teaching,[18] which have all been associated with reduced risk of burnout in some studies.[17] Studies of psychiatrists[19] and pediatricians[20] have shown a lower rate of burnout among physicians with more inpatient duties. Finally, a practice model involving a seemingly stable cadre of inpatient physicians has existed in Europe for decades,[2] indicating at least a degree of sustainability.

Information suggesting a higher rate of burnout among inpatient physicians could be used to target therapeutic interventions and to adjust schedules, whereas the opposite outcome could refute a pervasive myth. We therefore endeavored to summarize the literature on burnout among inpatient versus outpatient physicians in a systematic fashion, and to include data not only from the US hospitalist experience but also from other countries that have used a similar model for decades. Our primary hypothesis was that inpatient physicians experience more burnout than outpatient physicians.

It is important to distinguish burnout from depression, job dissatisfaction, and occupational stress, all of which have been studied extensively in physicians. Burnout, as introduced by Freudenberger[21] and further characterized by Maslach,[22] is a condition in which emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment combine to negatively affect work life (as opposed to clinical depression, which affects all aspects of life). Job satisfaction can correlate inversely with burnout, but it is a separate process[23] and the subject of a recent systematic review.[24] The importance of distinguishing burnout from job dissatisfaction is illustrated by a survey of head and neck surgeons, in which 97% of those surveyed indicated satisfaction with their jobs and 34% of the same group answered in the affirmative when asked if they felt burned out.[25]

One obstacle to the meaningful comparison of burnout prevalence across time, geography, and specialty is the myriad ways in which burnout is measured and reported. The oldest and most commonly used instrument to measure burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which contains 22 items assessing 3 components of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment).[26] Other measures include the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory[27] (19 items with the components personal burnout, work‐related burnout, and client‐related burnout), Utrecht Burnout Inventory[28] (20‐item modification of the MBI), Boudreau Burnout Questionnaire[29] (30 items), Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens und Erlebensmuster[30] (66‐item questionnaire assessing professional commitment, resistance to stress, and emotional well‐being), Shirom‐Melamed Burnout Measure[31] (22 items with subscales for physical fatigue, cognitive weariness, tension, and listlessness), and a validated single‐item questionnaire.[32]

METHODS

Electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, SCOPUS, and PubMed were undertaken for articles published from January 1, 1974 (the year in which burnout was first described by Freudenberger[21]) to 2012 (last accessed, September 12, 2012) using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms stress, psychological; burnout, professional; adaptation, psychological; and the keyword burnout. The same sources were searched to create another set for the MeSH terms hospitalists, physician's practice patterns, physicians/px, professional practice location, and the keyword hospitalist#. Where exact subject headings did not exist in databases, comparable subject headings or keywords were used. The 2 sets were then combined using the operator and. Abstracts from the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conferences were hand‐searched, as were reference lists from identified articles. To ensure that pertinent international literature was captured, there was no language restriction in the search.

A 2‐stage screening process was used. The titles and abstracts of all articles identified in the search were independently reviewed by 2 investigators (D.L.R. and K.J.C.) who had no knowledge of each other's results. An article was obtained when either reviewer deemed it worthy of full‐text review.

All full‐text articles were independently reviewed by the same 2 investigators. The inclusion criterion was the measurement of burnout in physicians who are stated to or can be reasonably assumed to spend the substantial majority of their clinical practice exclusively in either the inpatient or the outpatient setting. Studies of emergency department physicians or specialists who invariably spend substantial amounts of time in both settings (eg, surgeons, anesthesiologists) were excluded. Studies limited to trainees or nonphysicians were also excluded. For both stages of review, agreement between the 2 investigators was assessed by calculating the statistic. Disagreements about inclusion were adjudicated by a third investigator (A.I.B.).

Because our goal was to establish and compare the rate of burnout among US hospitalists and other inpatient physicians around the world, we included studies of hospitalists according to the definition in use at the time of the individual study, noting that the formal definition of a hospitalist has changed over the years.[33] Because practice patterns for physicians described as primary care physicians, family doctors, hospital doctors, and others differ substantially from country to country, we otherwise included only the studies where the practice location was stated explicitly or where the authors confirmed that their study participants either are known or can be reasonably assumed to spend more than 75% of their time caring for hospital inpatients, or are known or can be reasonably assumed to spend the vast majority of their time caring for outpatients.

Data were abstracted using a standardized form and included the measure of burnout used in the study, results, practice location of study subjects, and total number of study subjects. When data were not clear (eg, burnout measured but not reported by the authors, practice location of study subjects not clear), authors were contacted by email, or when no current email address could be located or no response was received, by telephone or letter. In instances where burnout was measured repeatedly over time or before and after a specific intervention, only the baseline measurement was recorded. Because all studies were expected to be nonrandomized, methodological quality was assessed using a version of the tool of Downs and Black,[34] adapted where necessary by omitting questions not applicable to the specific study type (eg randomization for survey studies)[35] and giving a maximum of 1 point for the inclusion of a power calculation.

Two a priori analyses were planned: (1) a statistical comparison of articles directly comparing burnout among inpatient and outpatient physicians, and (2) a statistical comparison of articles measuring burnout among inpatient physicians with articles measuring burnout among outpatient physicians by the most frequently reported measuremean subset scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment on the MBI.

The primary outcome measures were the differences between mean subset scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment on the MBI. All differences are expressed as (outpatient meaninpatient mean). The variance of each outcome was calculated with standard formulas.[36] To calculate the overall estimate, each study was weighted by the reciprocal of its variance. Studies with fewer than 10 subjects were excluded from statistical analysis but retained in the systematic review.

For studies that reported data for both inpatient and outpatient physicians (double‐armed studies), Cochran Q test and the I2 value were used to assess heterogeneity.[37, 38] Substantial heterogeneity was expected because these individual studies were conducted for different populations in different settings with different study designs, and this expectation was confirmed statistically. Therefore, we used a random effects model to estimate the overall effect, providing a conservative approach that accounted for heterogeneity among studies.[39]

To assess the durability of our findings, we performed separate multivariate meta‐regression analyses by including single‐armed studies only and including both single‐armed and double‐armed studies. For these meta‐regressions, means were again weighted by the reciprocal of their variances, and the arms of 2‐armed studies were considered separately. This approach allowed us to generate an estimate of the differences between MBI subset scores from studies that did not include such an estimate when analyzed separately.[40]

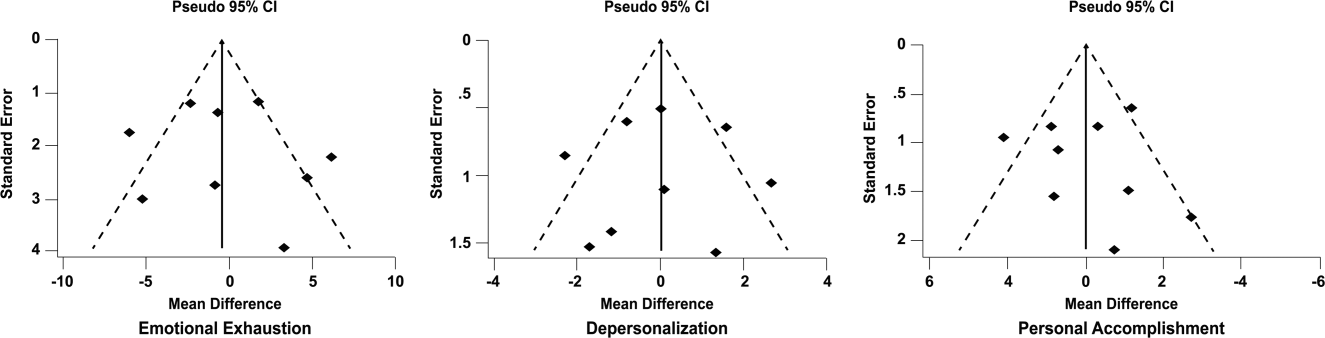

We examined the potential for publication bias in double‐armed studies by constructing a funnel plot, in which mean scores were plotted against their standard errors.[41] The trim‐and‐fill method was used to determine whether adjustment for publication bias was necessary. In addition, Begg's rank correlation test[42] was completed to test for statistically significant publication bias.

Stata 10.0 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for data analyses. A P value of 0.05 or less was deemed statistically significant. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis checklist was used for the design and execution of the systematic review and meta‐analysis.[43]

Subgroup analyses based on location were undertaken a posteriori. All data (double‐armed meta‐analysis, meta‐regression of single‐armed studies, and meta‐regression of single‐ and double‐armed studies) were analyzed by location (United States vs other; United States vs Europe vs other).

RESULTS

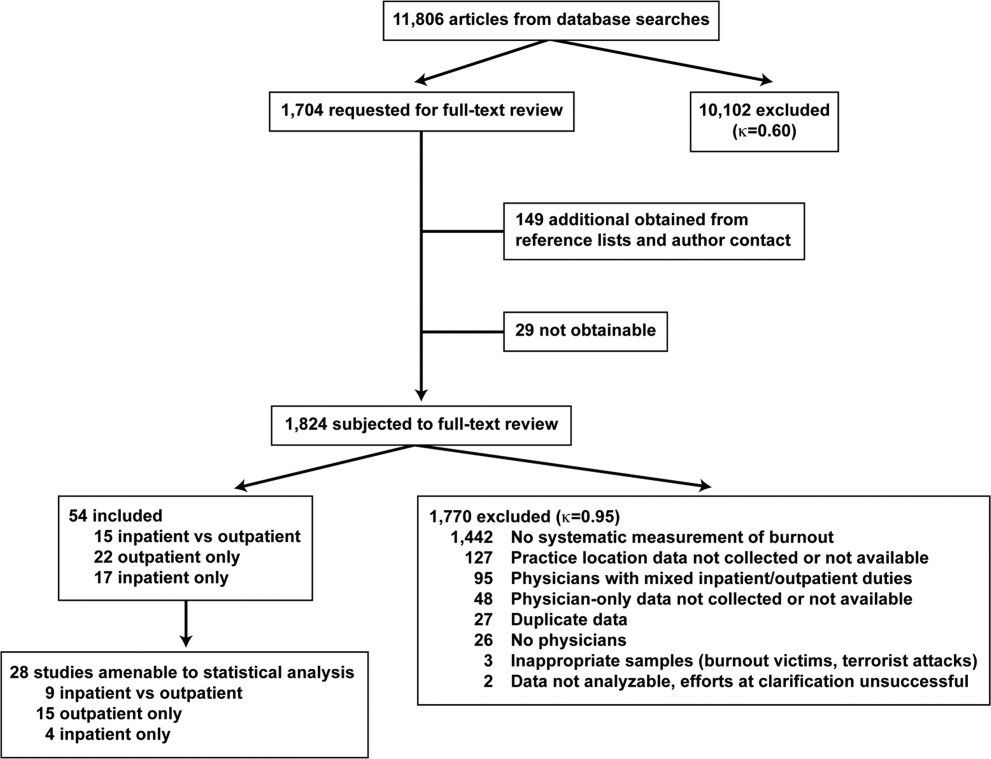

The search results are outlined in Figure 1. In total, 1704 articles met the criteria for full‐text review. A review of pertinent reference lists and author contacts led to the addition of 149 articles. Twenty‐nine references could not be located by any means, despite repeated attempts. Therefore, 1824 articles were subjected to full‐text review by the 2 investigators.

Initially, 57 articles were found that met criteria for inclusion. Of these, 2 articles reported data in formats that could not be interpreted.[44, 45] When efforts to clarify the data with the authors were unsuccessful, these studies were excluded. A study specifically designed to assess the response of physicians to a recent series of terrorist attacks[46] was excluded a posteriori because of lack of generalizability. Of the other 54 studies, 15 reported burnout data on both outpatient physicians and inpatient physicians, 22 reported data on outpatient physicians only, and 17 reported data on inpatient physicians only. Table 1 summarizes the results of the 37 studies involving outpatient physicians; Table 2 summarizes the 32 studies involving inpatient physicians.

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Study Population and Location | Instrument | No. of Participants | EE Score (SD)a | DP Score (SD) | PA Score (SD) | Other Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Schweitzer, 1994[12] | Young physicians of various specialties in South Africa | Single‐item survey | 7 | 6 (83%) endorsed burnout | |||

| Aasland, 1997 [54]b | General practitioners in Norway | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 15) | 298 | 2.65 (0.80) | 1.90 (0.59) | 3.45 (0.40) | |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | General practitioners in Italy | MBI | 182 | 18.49 (11.49) | 6.11 (5.86) | 38.52 (7.60) | |

| McManus, 2000 [59]b | General practitioners in United Kingdom | Modified MBI (9 items; scale, 06) | 800 | 8.34 (4.39) | 3.18 (3.40) | 14.16 (2.95) | |

| Yaman, 2002 [60] | General practitioners in 8 European nations | MBI | 98 | 25.1 (8.50) | 7.3 (4.92) | 34.5 (7.67) | |

| Cathbras, 2004 [61] | General practitioners in France | MBI | 306 | 21.85 (12.4) | 9.13 (6.7) | 38.7 (7.1) | |

| Goehring, 2005 [63] | General practitioners, general internists, pediatricians in Switzerland | MBI | 1755 | 17.9 (9.8) | 6.5 (4.7) | 39.6 (6.5) | |

| Esteva, 2006 [64] | General practitioners, pediatricians in Spain | MBI | 261 | 27.4 (11.8) | 10.07 (6.4) | 35.9 (7.06) | |

| Gandini, 2006 [65]b | Physicians of various specialties in Argentina | MBI | 67 | 31.0 (13.8) | 10.2 (6.6) | 38.4 (6.8) | |

| Ozyurt, 2006 [66] | General practitioners in Turkey | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 04) | 55 | 15.23 (5.80) | 4.47 (3.31) | 23.38 (4.29) | |

| Deighton, 2007 [67]b | Psychiatrists in several German‐speaking nations | MBI | 19 | 30.68 (9.92) | 13.42 (4.23) | 37.16 (3.39) | |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68]b | Palliative care physicians in Australia | MBI | 21 | 14.95 (9.14) | 3.95 (3.40) | 38.90 (2.88) | |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69]b | Psychiatrists in 5 European nations | MBI | 22 | 19.41 (8.08) | 6.68 (4.93) | 39.00 (4.40) | |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56]b | Physicians of various specialties in Argentina | Author‐designed instrument | 33 | 26 (78.8%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 6.15 symptoms per physician | |||

| Voltmer, 2007 [57]b | Physicians of various specialties in Germany | AVEM | 46 | 11 (23.9%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | |||

| dm, 2008 [70]b | Physicians of various specialties in Hungary | MBI | 163 | 17.45 (11.12) | 4.86 (4.91) | 36.56 (7.03) | |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71]b | Dialysis physicians in Italy | Author‐designed instrument | 54 | Work: 2.6 (1.5), Material: 3.1 (2.1), Climate: 3.0 (1.1), Objectives: 3.4 (1.6), Quality: 2.2 (1.5), Justification: 3.2 (2.0) | |||

| Lee, 2008 [49]b | Family physicians in Canada | MBI | 123 | 26.26 (9.53) | 10.20 (5.22) | 38.43 (7.34) | |

| Truchot, 2008 [72] | General practitioners in France | MBI | 259 | 25.4 (11.7) | 7.5 (5.5) | 36.5 (7.1) | |

| Twellaar, 2008 [73]b | General practitioners in the Netherlands | Utrecht Burnout Inventory | 349 | 2.06 (1.11) | 1.71 (1.05) | 5.08 (0.77) | |

| Arigoni, 2009 [17] | General practitioners, pediatricians in Switzerland | MBI | 258 | 22.8 (12.0) | 6.9 (6.1) | 39.0 (7.2) | |

| Bernhardt, 2009 [75] | Clinical geneticists in United States | MBI | 72 | 25.8 (10.01)c | 10.9 (4.16)c | 34.8 (5.43)c | |

| Bressi, 2009 [76]b | Psychiatrists in Italy | MBI | 53 | 23.15 (11.99) | 7.02 (6.29) | 36.41 (7.54) | |

| Krasner, 2009 [77] | General practitioners in United States | MBI | 60 | 26.8 (10.9)d | 8.4 (5.1)d | 40.2 (5.3)d | |

| Lasalvia, 2009 [55]b | Psychiatrists in Italy | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06) | 38 | 2.37 (1.27) | 1.51 (1.15) | 4.46 (0.87) | |

| Peisah, 2009 [79]b | Physicians of various specialties in Australia | MBI | 28 | 13.92 (9.24) | 3.66 (3.95) | 39.34 (8.55) | |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80]b | Physicians of various specialties in United States | MBI | 408 | 20.5 (11.10) | 4.3 (4.74) | 40.8 (6.26) | |

| Zantinge, 2009 [81] | General practitioners in the Netherlands | Utrecht Burnout Inventory | 126 | 1.58 (0.79) | 1.32 (0.72) | 4.27 (0.77) | |

| Voltmer, 2010 [83]b | Psychiatrists in Germany | AVEM | 526 | 114 (21.7%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | |||

| Maccacaro, 2011 [85]b | Physicians of various specialties in Italy | MBI | 42 | 14.31 (11.98) | 3.62 (4.95) | 38.24 (6.22) | |

| Lucas, 2011 [84]b | Outpatient physicians periodically staffing an academic hospital teaching service in United States | MBI (EE only) | 30 | 24.37 (14.95) | |||

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87]b | General internists in United States | MBI | 447 | 25.4 (14.0) | 7.5 (6.3) | 41.4 (6.0) | |

| Kushnir, 2004 [62] | General practitioners and pediatricians in Israel | MBI (DP only) and SMBM | 309 | 9.15 (3.95) | SMBM mean (SD), 2.73 per item (0.86) | ||

| Vela‐Bueno, 2008 [74]b | General practitioners in Spain | MBI | 240 | 26.91 (11.61) | 9.20 (6.35) | 35.92 (7.92) | |

| Lesic, 2009 [78]b | General practitioners in Serbia | MBI | 38 | 24.71 (10.81) | 7.47 (5.51) | 37.21 (7.44) | |

| Demirci, 2010 [82]b | Medical specialists related to oncology practice in Hungary | MBI | 26 | 23.31 (11.2) | 6.46 (5.7) | 37.7 (8.14) | |

| Putnik, 2011 [86]b | General practitioners in Hungary | MBI | 370 | 22.22 (11.75) | 3.66 (4.40) | 41.40 (6.85) | |

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Study Population and Location | Instrument | No. of Participants | EE Score (SD)a | DP Score (SD) | PA Score (SD) | Other Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Varga, 1996 [88] | Hospital doctors in Spain | MBI | 179 | 21.61b | 7.33b | 35.28b | |

| Aasland, 1997 [54] | Hospital doctors in Norway | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 15) | 582 | 2.39 (0.80) | 1.81 (0.65) | 3.51 (0.46) | |

| Bargellini, 2000 [89] | Hospital doctors in Italy | MBI | 51 | 17.45 (9.87) | 7.06 (5.54) | 35.33 (7.90) | |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | Hospital doctors in Italy | MBI | 146 | 16.17 (9.64) | 5.32 (4.76) | 38.71 (7.28) | |

| Hoff, 2001 [33] | Hospitalists in United States | Single‐item surveyc | 393 | 12.9% burned out (>4/5), 24.9% at risk for burnout (34/5), 62.2% at no current risk (mean, 2.86 on 15 scale) | |||

| Trichard, 2005 [90] | Hospital doctors in France | MBI | 199 | 16 (10.7) | 6.6 (5.7) | 38.5 (6.5) | |

| Gandini, 2006 [65]d | Hospital doctors in Argentina | MBI | 290 | 25.0 (12.7) | 7.9 (6.2) | 40.1 (7.0) | |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68]d | Palliative care doctors in Australia | MBI | 14 | 18.29 (14.24) | 5.29 (5.89) | 38.86 (3.42) | |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69]d | Psychiatrists in 5 European nations | MBI | 18 | 18.56 (9.32) | 5.50 (3.79) | 39.08 (5.39) | |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56]d | Hospital doctors in Argentina | Author‐designed instrument | 3 | 3 (100%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 8.67 symptoms per physician | |||

| Voltmer, 2007 [57]d | Hospital doctors in Germany | AVEM | 271 | 77 (28.4%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | |||

| dm, 2008 [70]b | Physicians of various specialties in Hungary | MBI | 194 | 19.23 (10.79) | 4.88 (4.61) | 35.26 (8.42) | |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71]d | Dialysis physicians in Italy | Author‐designed instrument | 62 | Work, mean (SD), 3.1 (1.4); Material, mean (SD), 3.3 (1.5); Climate, mean (SD), 2.9 (1.1); Objectives, mean (SD), 2.5 (1.5); Quality, mean (SD), 3.0 (1.1); Justification, mean (SD), 3.1 (2.1) | |||

| Fuss, 2008 [91]d | Hospital doctors in Germany | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | 292 | Mean Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, mean (SD), 46.90 (18.45) | |||

| Marner, 2008 [92]d | Psychiatrists and 1 generalist in United States | MBI | 9 | 20.67 (9.75) | 7.78 (5.14) | 35.33 (6.44) | |

| Shehabi, 2008 [93]d | Intensivists in Australia | Modified MBI (6 items; scale, 15) | 86 | 2.85 (0.93) | 2.64 (0.85) | 2.58 (0.83) | |

| Bressi, 2009 [76]d | Psychiatrists in Italy | MBI | 28 | 17.89 (14.46) | 5.32 (7.01) | 34.57 (11.27) | |

| Brown, 2009 [94] | Hospital doctors in Australia | MBI | 12 | 22.25 (8.59) | 6.33 (2.71) | 39.83 (7.31) | |

| Lasalvia, 2009 [55]d | Psychiatrists in Italy | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06) | 21 | 1.95 (1.04) | 1.35 (0.85) | 4.46 (1.04) | |

| Peisah, 2009 [79]d | Hospital doctors in Australia | MBI | 62 | 20.09 (9.91) | 6.34 (4.90) | 35.06 (7.33) | |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80]d | Hospitalists and intensivists in United States | MBI | 19 | 25.2 (11.59) | 4.4 (3.79) | 38.5 (8.04) | |

| Tunc, 2009 [95] | Hospital doctors in Turkey | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 04) | 62 | 1.18 (0.78) | 0.81 (0.73) | 3.10 (0.59)e | |

| Cocco, 2010 [96]d | Hospital geriatricians in Italy | MBI | 38 | 16.21 (11.56) | 4.53 (4.63) | 39.13 (7.09) | |

| Doppia, 2011 [97]d | Hospital doctors in France | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | 1,684 | Mean work‐related burnout score, 2.72 (0.75) | |||

| Glasheen, 2011 [98] | Hospitalists in United States | Single‐item survey | 265 | Mean, 2.08 on 15 scale 62 (23.4%) burned out | |||

| Lucas, 2011 [84]d | Academic hospitalists in United States | MBI (EE only) | 26 | 19.54 (12.85) | |||

| Thorsen, 2011 [99] | Hospital doctors in Malawi | MBI | 2 | 25.5 (4.95) | 8.5 (6.36) | 25.0 (5.66) | |

| Hinami, 2012 [50]d | Hospital doctors in United States | Single‐item survey | 793 | Mean, 2.24 on 15 scale 261 (27.2%) burned out | |||

| Quenot, 2012 [100]d | Intensivists in France | MBI | 4 | 33.25 (4.57) | 13.50 (5.45) | 35.25 (4.86) | |

| Ruitenburg, 2012 [101] | Hospital doctors in the Netherlands | MBI (EE and DP only) | 214 | 13.3 (8.0) | 4.5 (4.1) | ||

| Seibt, 2012 [102]d | Hospital doctors in Germany | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06, reported per item rather than totals) | 2,154 | 2.2 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.2) | 5.1 (0.9) | |

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87]d | Hospitalists in United States | MBI | 130 | 24.7 (12.5) | 9.1 (6.9) | 39.0 (7.6) | |

Table 3 summarizes the results of the 15 studies that reported burnout data for both inpatient and outpatient physicians, allowing direct comparisons to be made. Nine studies reported MBI subset totals with standard deviations, 2 used different modifications of the MBI, 2 used different author‐derived measures, 1 used only the emotional exhaustion subscale of the MBI, and 1 used the Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens und Erlebensmuster. Therefore, statistical comparison was attempted only for the 9 studies reporting comparable MBI data, comprising burnout data on 1390 outpatient physicians and 899 inpatient physicians.

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Location | Instrument | Inpatient‐Based Physicians | Outpatient‐Based Physicians | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Results, Score (SD)a | No. | Results, Score (SD)a | |||

| ||||||

| Aasland, 1997 [54]b | Norway | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 15) | 582 | EE, 2.39 (0.80); DP, 1.81 (0.65); PA, 3.51 (0.46) | 298 | EE, 2.65 (0.80); DP, 1.90 (0.59); PA, 3.45 (0.40) |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | Italy | MBI | 146 | EE, 16.17 (9.64); DP, 5.32 (4.76); PA, 38.71 (7.28) | 182 | EE, 18.49 (11.49); DP, 6.11 (5.86); PA, 38.52 (7.60) |

| Gandini, 2006 [65]b | Argentina | MBI | 290 | EE, 25.0 (12.7);DP, 7.9 (6.2); PA, 40.1 (7.0) | 67 | EE, 31.0 (13.8); DP, 10.2 (6.6); PA, 38.4 (6.8) |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68]b | Australia | MBI | 14 | EE, 18.29 (14.24); DP, 5.29 (5.89); PA, 38.86 (3.42) | 21 | EE, 14.95 (9.14); DP, 3.95 (3.40); PA, 38.90 (2.88) |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69]b | 5 European nations | MBI | 18 | EE, 18.56 (9.32); DP, 5.50 (3.79); PA, 39.08 (5.39) | 22 | EE, 19.41 (8.08); DP, 6.68 (4.93); PA, 39.00 (4.40) |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56]b | Argentina | Author‐designed instrument | 3 | 3 (100%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 8.67 symptoms per physician | 33 | 26 (78.8%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 6.15 symptoms per physician |

| Voltmer, 2007 [57]b | Germany | AVEM | 271 | 77 (28.4%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | 46 | 11 (23.9%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern |

| dm, 2008 [70]b | Hungary | MBI | 194 | EE, 19.23 (10.79); DP, 4.88 (4.61); PA, 35.26 (8.42) | 163 | EE, 17.45 (11.12); DP, 4.86 (4.91); PA, 36.56 (7.03) |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71]b | Italy | Author‐designed instrument | 62 | Work: 3.1 (1.4); material: 3.3 (1.5); climate: 2.9 (1.1); objectives: 2.5 (1.5); quality: 3.0 (1.1); justification: 3.1 (2.1) | 54 | Work: 2.6 (1.5); material: 3.1 (2.1); climate: 3.0 (1.1); objectives: 3.4 (1.6); quality: 2.2 (1.5); justification: 3.2 (2.0) |

| Bressi, 2009 [76]b | Italy | MBI | 28 | EE, 17.89 (14.46); DP, 5.32 (7.01); PA, 34.57 (11.27) | 53 | EE, 23.15 (11.99); DP, 7.02 (6.29); PA, 36.41 (7.54) |

| Lasalvia, 2009[55]b | Italy | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06) | 21 | EE, 1.95 (1.04); DP, 1.35 (0.85); PA, 4.46 (1.04) | 38 | EE, 2.37 (1.27); DP, 1.51 (1.15); PA, 4.46 (0.87) |

| Peisah, 2009 [79]b | Australia | MBI | 62 | EE, 20.09 (9.91); DP, 6.34 (4.90); PA, 35.06 (7.33) | 28 | EE, 13.92 (9.24); DP, 3.66 (3.95); PA, 39.34 (8.55) |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80]b | United States | MBI | 19 | EE, 25.2 (11.59); DP, 4.4 (3.79); PA, 38.5 (8.04) | 408 | EE, 20.5 (11.10); DP, 4.3 (4.74); PA, 40.8 (6.26) |

| Lucas, 2011 [84]b | United States | MBI (EE only) | 26 | EE, 19.54 (12.85) | 30 | EE, 24.37 (14.95) |

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87]b | United States | MBI | 130 | EE, 24.7 (12.5); DP, 9.1 (6.9); PA, 39.0 (7.6) | 447 | EE, 25.4 (14.0); DP, 7.5 (6.3); PA, 41.4 (6.0) |

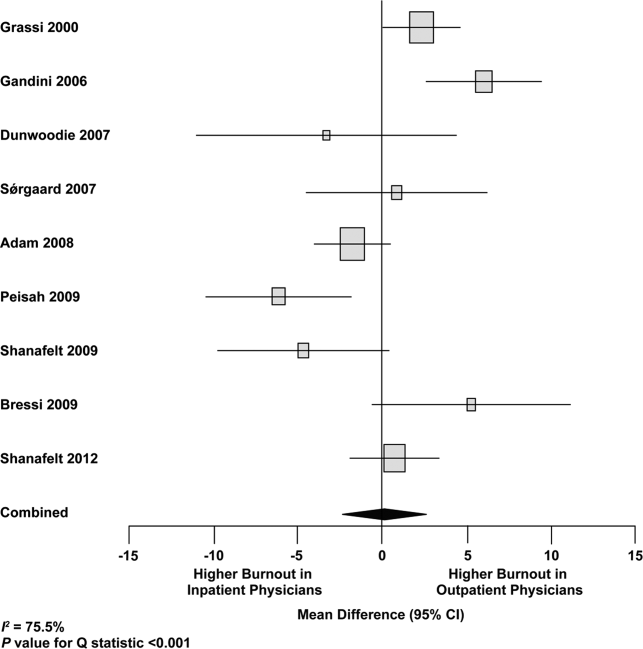

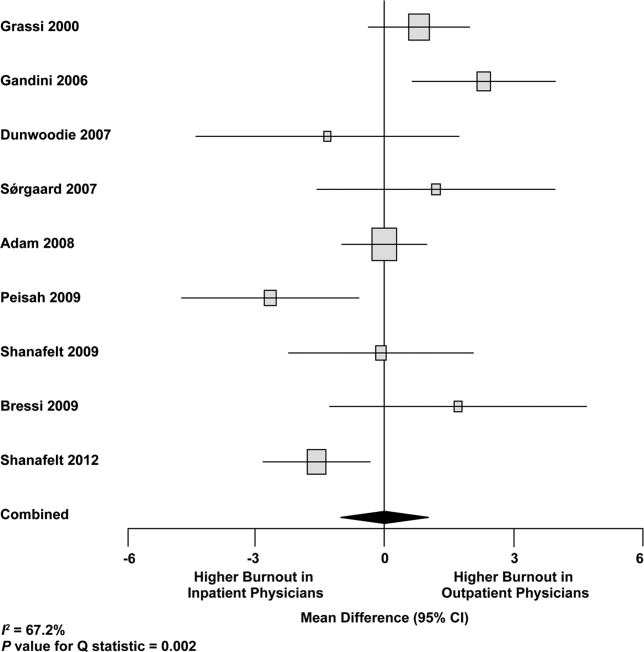

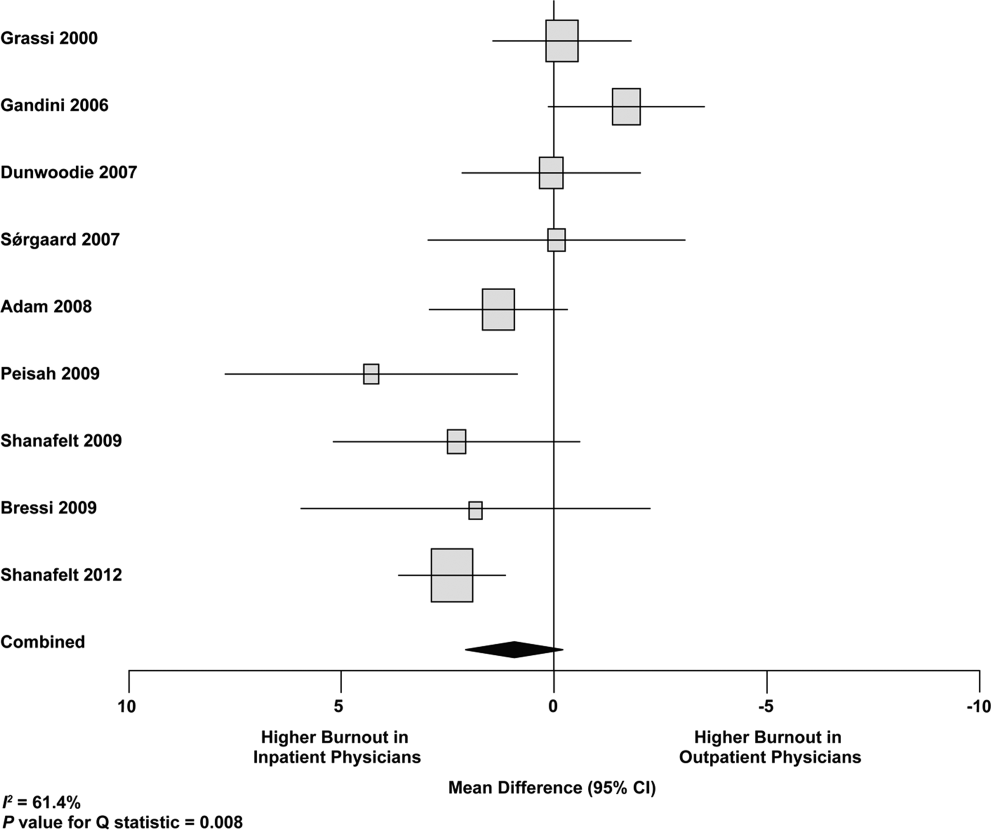

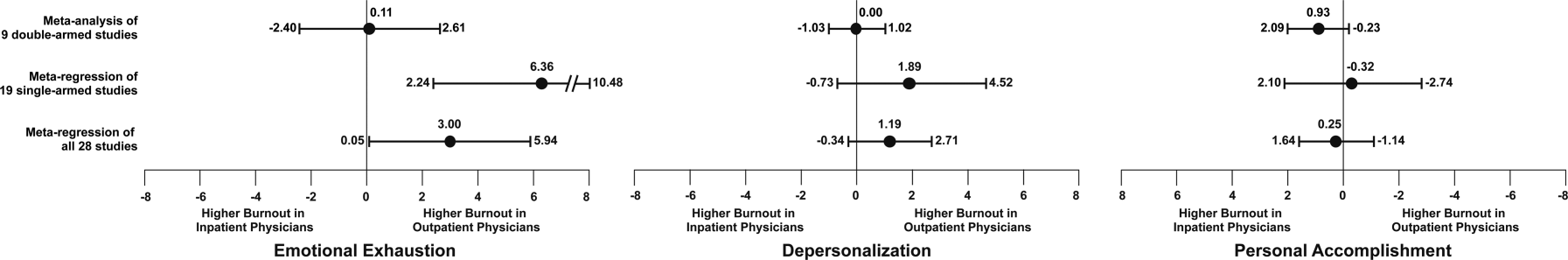

Figure 2 shows that no significant difference existed between the groups regarding emotional exhaustion (mean difference, 0.11 points on a 54‐point scale; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.40 to 2.61; P=0.94). In addition, there was no significant difference between the groups regarding depersonalization (Figure 3; mean difference, 0.00 points on a 30‐point scale; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.02; P=0.99) and personal accomplishment (Figure 4; mean difference, 0.93 points on a 48‐point scale; 95% CI, 0.23 to 2.09; P=0.11).

We used meta‐regression to allow the incorporation of single‐armed MBI studies. Whether single‐armed studies were analyzed separately (15 outpatient studies comprising 3927 physicians, 4 inpatient studies comprising 300 physicians) or analyzed with double‐armed studies (24 outpatient arms comprising 5318 physicians, 13 inpatient arms comprising 1301 physicians), the lack of a significant difference between the groups persisted for the depersonalization and personal accomplishment scales (Figure 5). Emotional exhaustion was significantly higher in outpatient physicians when single‐armed studies were considered separately (mean difference, 6.36 points; 95% CI, 2.24 to 10.48; P=0.002), and this difference persisted when all studies were combined (mean difference, 3.00 points; 95% CI, 0.05 to 5.94, P=0.046).

Subgroup analysis by geographic location showed US outpatient physicians had a significantly higher personal accomplishment score than US inpatient physicians (mean difference, 2.38 points; 95% CI, 1.22 to 3.55; P0.001) in double‐armed studies. This difference did not persist when single‐armed studies were included through meta‐regression (mean difference, 0.55 points, 95% CI, 4.30 to 5.40, P=0.83).

Table 4 demonstrates that methodological quality was generally good from the standpoint of the reporting and bias subsections of the Downs and Black tool. External validity was scored lower for many studies due to the use of convenience samples and lack of information about physicians who declined to participate.

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Reporting | External Validity | Internal Validity: Bias | Internal Validity: Confounding | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schweitzer, 1994 [12] | 5 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Varga, 1996 [88] | 5 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Aasland, 1997 [54] | 3 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Bargellini, 2000 [89] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| McManus, 2000 [59] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Hoff, 2001 [33] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 2 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Yaman, 2002 [60] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Cathbras, 2004 [61] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Kushnir, 2004 [62] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Goehring, 2005 [63] | 6 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Trichard, 2005 [90] | 3 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Esteva, 2006 [64] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Gandini, 2006 [65] | 6 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Ozyurt, 2006 [66] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Deighton, 2007 [67] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 1 of 1 point |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56] | 4 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Voltmer, 2007 [57] | 4 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| dm, 2008 [70] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 2 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Fuss, 2008 [91] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Lee, 2008 [49] | 4 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 1 of 1 point |

| Marner, 2008 [92] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Shehabi, 2008 [93] | 3 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Truchot, 2008 [72] | 5 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Twellaar, 2008 [73] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Vela‐Bueno, 2008 [74] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Arigoni, 2009 [17] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Bernhardt, 2009 [75] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Bressi, 2009 [76] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Brown, 2009 [94] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Krasner, 2009 [77] | 9 of 11 points | 0 of 3 points | 6 of 7 points | 1 of 2 points | 1 of 1 point |

| Lasalvia, 2009 [55] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Lesic, 2009 [78] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Peisah, 2009 [79] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Tunc, 2009 [95] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Zantinge, 2009 [81] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Cocco, 2010 [96] | 4 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Demirci, 2010 [82] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Voltmer, 2010 [83] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Doppia, 2011 [97] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Glasheen, 2011 [98] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Lucas, 2011 [84] | 10 of 11 points | 2 of 3 points | 7 of 7 points | 5 of 6 points | 1 of 1 point |

| Maccacaro, 2011 [85] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Putnik, 2011 [86] | 6 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Thorsen, 2011 [99] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Hinami, 2012 [50] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 1 of 1 point |

| Quenot, 2012 [100] | 8 of 11 points | 1 of 3 points | 6 of 7 points | 1 of 2 points | 0 of 1 point |

| Ruitenburg, 2012 [101] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Seibt, 2012 [102] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

Funnel plots were used to evaluate for publication bias in the meta‐analysis of the 8 double‐armed studies (Figure 6). We found no significant evidence of bias, which was supported by Begg's test P values of 0.90 for emotional exhaustion, >0.99 for depersonalization, and 0.54 for personal accomplishment. A trim‐and‐fill analysis determined that no adjustment was necessary.

DISCUSSION

There appears to be no support for the long‐held belief that inpatient physicians are particularly prone to burnout. Among studies for which practice location was stated explicitly or could be obtained from the authors, and who used the MBI, no differences were found among inpatient and outpatient physicians with regard to depersonalization or personal accomplishment. This finding persisted whether double‐armed studies were compared directly, single‐armed studies were incorporated into this analysis, or single‐armed studies were analyzed separately. Outpatient physicians had a higher degree of emotional exhaustion when all studies were considered.

There are several reasons why outpatient physicians may be more prone to emotional exhaustion than their inpatient colleagues. Although it is by no means true that all inpatient physicians work in shifts, the increased availability of shift work may allow some inpatient physicians to better balance their professional and personal lives, a factor of work with which some outpatient physicians have struggled.[47] Inpatient practice may also afford more opportunity for teamwork, a factor that has been shown to correlate with reduced burnout.[48] When surveyed about burnout, outpatient physicians have cited patient volumes, paperwork, medicolegal concerns, and lack of community support as factors.[49] Inpatient physicians are not immune to these forces, but they arguably experience them to different degrees.

The absence of a higher rate of depersonalization among inpatient physicians is particularly reassuring in light of concerns expressed with the advent of US hospital medicinethat some hospitalists would be prone to viewing patients as an impediment to the efficient running of the hospital,[2] the very definition of depersonalization.

Although the difference in the whole sample was not statistically significant, the consistent tendency toward a greater sense of personal accomplishment among outpatient physicians is also noteworthy, particularly because post hoc subgroup analysis of US physicians did show statistical significance in both 2‐armed studies. Without detailed age data for the physicians in each study, we could not separate the possible impact of age on personal accomplishment; hospital medicine is a newer specialty staffed by generally younger physicians, and hospitalists may not have had time to develop a sense of accomplishment. When surveyed about job satisfaction, hospitalists have also reported the feeling that they were treated as glorified residents,[50] a factor that, if shared by other inpatient physicians, must surely affect their sense of personal accomplishment. The lack of longitudinal care for patients and the substantial provision of end‐of‐life care also may diminish the sense of personal accomplishment among inpatient physicians.

Another important finding from this systematic review is the marked heterogeneity of the instruments used to measure physician burnout. Many of the identified studies could not be subjected to meta‐analysis because of their use of differing burnout measures. Drawing more substantial conclusions about burnout and practice location is limited by the fact that, although the majority of studies used the full MBI, the largest study of European hospital doctors used the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the studies thus far of US hospitalists have used single‐item surveys or portions of the MBI. Not reflected in this review is the fact that a large study of US burnout and job satisfaction[51] did not formally address practice location (M. Linzer, personal communication, August 2012). Similarly, a large study of British hospital doctors[52] is not included herein because many of the physicians involved had substantial outpatient duties (C. Taylor, personal communication, July 2012). Varying burnout measures have complicated a previous systematic review of burnout in oncologists.[53] Two studies that directly compared inpatient and outpatient physicians but that were excluded from our statistical analysis because of their modified versions of the MBI,[54, 55] showed higher burnout scores in outpatient physicians. Two other studies that provided direct inpatient versus outpatient comparisons but that used alternative burnout measures[56, 57] showed a greater frequency of burnout in inpatient physicians, but of these, 1 study[56] involved only 3 inpatient physicians.

Several limitations of our study should be considered. Although we endeavored to obtain information from authors (with some success) about specific local practice patterns and eliminated many studies because of incomplete data or mixed practice patterns (eg, general practitioners who take frequent hospital calls, hospital physicians with extensive outpatient duties in a clinic attached to their hospital), it remains likely that many physicians identified as outpatient provided some inpatient care (attending a few weeks per year on a teaching service, for example) and that some physicians identified as inpatient have minimal outpatient duties.

More importantly, the dataset analyzed is heterogeneous. Studies of the incidence of burnout are naturally observational and therefore not randomized. Inclusion of international studies is necessary to answer the research question (because published data on US hospitalists are sparse) but naturally introduces differences in practice settings, local factors, and other factors for which we cannot possibly account fully.

Our meta‐analysis therefore addressed a broad question about burnout among inpatient and outpatient physicians in various diverse settings. Applying it to any 1 population (including US hospitalists) is, by necessity, imprecise.

Post hoc analysis should be viewed with caution. For example, the finding of a statistical difference between US inpatient and outpatient physicians with regard to personal accomplishment score is compelling from the standpoint of hypothesis generation. However, it is worth bearing in mind that this analysis contained only 2 studies, both by the same primary author, and compared 855 outpatient physicians to only 149 hospitalists. This difference was no longer significant when 2 outpatient studies were added through meta‐regression.

Finally, the specific focus of this study on practice location precluded comparison with emergency physicians and anesthesiologists, 2 specialist types that have been the subject of particularly robust burnout literature. As the literature on hospitalist burnout becomes more extensive, comparative studies with these groups and with intensivists might prove instructive.

In summary, analysis of 24 studies comprising data on 5318 outpatient physicians and 1301 inpatient physicians provides no support for the commonly held belief that hospital‐based physicians are particularly prone to burnout. Outpatient physicians reported higher emotional exhaustion. Further studies of the incidence and severity of burnout according to practice location are indicated. We propose that in future studies, to avoid the difficulties with statistical analysis summarized herein, investigators ask about and explicitly report practice location (inpatient vs outpatient vs both) and report mean MBI subset data and standard deviations. Such information about US hospitalists would allow comparison with a robust (if heterogeneous) international literature on burnout.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all of the study authors who contributed clarification and guidance for this project, particularly the following authors who provided unpublished data for further analysis: Olaf Aasland, MD; Szilvia dm, PhD; Annalisa Bargellini, PhD; Cinzia Bressi, MD, PhD; Darrell Campbell Jr, MD; Ennio Cocco, MD; Russell Deighton, PhD; Senem Demirci Alanyali, MD; Biagio Di Iorio, MD, PhD; David Dunwoodie, MBBS; Sharon Einav, MD; Madeleine Estryn‐Behar, PhD; Bernardo Gandini, MD; Keiki Hinami, MD; Antonio Lasalvia, MD, PhD; Joseph Lee, MD; Guido Maccacaro, MD; Swati Marner, EdD; Chris McManus, MD, PhD; Carmelle Peisah, MBBS, MD; Katarina Putnik, MSc; Alfredo Rodrguez‐Muoz, PhD; Yahya Shehabi, MD; Evelyn Sosa Oberlin, MD; Jean Karl Soler, MD, MSc; Knut Srgaard, PhD; Cath Taylor; Viva Thorsen, MPH; Mascha Twellaar, MD; Edgar Voltmer, MD; Colin West, MD, PhD; and Deborah Whippen. The authors also thank the following colleagues for their help with translation: Dusanka Anastasijevic (Norwegian); Joyce Cheung‐Flynn, PhD (simplified Chinese); Ales Hlubocky, MD (Czech); Lena Jungheim, RN (Swedish); Erez Kessler (Hebrew); Kanae Mukai, MD (Japanese); Eliane Purchase (French); Aaron Shmookler, MD (Russian); Jan Stepanek, MD (German); Fernando Tondato, MD (Portuguese); Laszlo Vaszar, MD (Hungarian); and Joseph Verheidje, PhD (Dutch). Finally, the authors thank Cynthia Heltne and Diana Rogers for their expert and tireless library assistance, Bonnie Schimek for her help with figures, and Cindy Laureano and Elizabeth Jones for their help with author contact.