Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

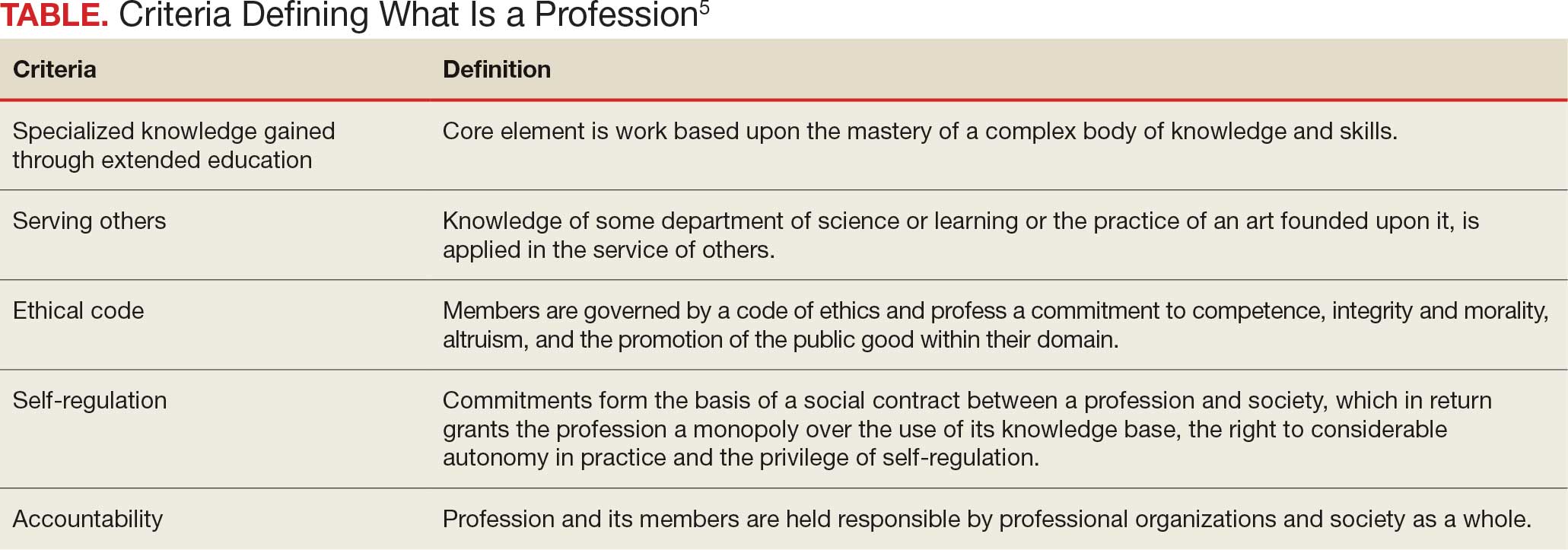

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.