Inpatient Management of Diabetic Foot Infections: A Review of the Guidelines for Hospitalists

Diabetic foot infections (DFIs) are common and represent the leading cause for hospitalization among diabetic complications. Without proper management, DFIs may lead to amputation, which is associated with a decreased quality of life and increased mortality. However, there is currently significant variation in the management of DFIs, and many providers fail to perform critical prevention and assessment measures. In this review, we will provide an overview of the diagnosis, management, and discharge planning of hospitalized patients with DFIs to guide hospitalists in the optimal inpatient care of patients with this condition.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Diabetic foot infection (DFI) is a common result of diabetes and represents the most frequent complication requiring hospitalization and lower extremity amputation.1,2 Hospital discharges related to diabetic lower extremity ulcers increased from 72,000 in 1988 to 113,000 in 2007,3 and admissions related to infection rose 30% between 2005 and 2010.2 Ulceration and amputation are associated with a 40% to 50% 5-year mortality rate.4,5

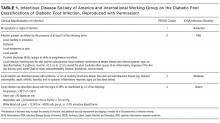

Aggressive risk-factor management and interprofessional care can significantly reduce major amputations and mortality.6-13 Consistent and high-quality care for patients admitted with DFI is essential for optimizing outcomes; however, management varies widely, and critical assessment and prevention measures are often not employed by providers.14 This review synthesizes recommendations from existing guidelines to provide an overview of the best practices for the diagnosis, management, and discharge of DFI in the hospital setting (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure).

DETECTION AND STAGING OF INFECTION

The first step in the management of a DFI is a careful assessment of the presence and depth of infection.15 The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend using at least 2 signs of classic inflammation (erythema, warmth, swelling, tenderness, or pain) or purulent drainage to diagnose soft tissue infection.1,15,16 Patients with ischemia may present atypically, with nonpurulent secretions, friable or discolored granulation tissue, undermining of wound edges, and foul odor. 1,15,16 Additional risk factors for DFI include ulceration for more than 30 days, recurrent foot ulcers, a traumatic foot wound, severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in the affected limb (ankle brachial index [ABI] <0.4), prior lower extremity amputation, loss of protective sensation, end-stage renal disease, and a history of walking barefoot.15,17,18

CRITERIA FOR HOSPITALIZATION

In practice, the decision to admit is based on clinical and systems-based drivers (Supplementary Table 2). The IDSA and IWGDF guidelines recommend hospitalization for patients with severe (PEDIS grade 4) infection, moderate (PEDIS grade 3) infection with certain complications (eg, severe PAD or lack of home support), an inability to comply with required outpatient treatment, lack of improvement with outpatient therapy, or presence of metabolic or hemodynamic instability.1,15 Clinicians must also consider the need for surgical debridement or complex antibiotic choices due to allergies and comorbidities. Hospitalists may also consider admission in cases in which outpatient follow-up cannot be easily arranged (eg, uninsured patients).

Outpatient management may be appropriate for patients with mild infections who are willing to be reassessed within 72 hours, or sooner if the infection worsens.23 For patients with moderate infections (eg, osteomyelitis without systemic signs of infection), access to an outpatient interprofessional DFI care team can potentially decrease the need for admission.

DIAGNOSIS OF OSTEOMYELITIS

Clinical features that raise suspicion for osteomyelitis include ulceration for at least 6 weeks with appropriate wound care and offloading, wound extension to the bone or joint, exposed bone, ulcers larger than 2 cm2, previous history of a wound, multiple wounds, and appearance of a sausage digit.15

The gold standard for diagnosis of osteomyelitis is a bone biopsy with histology. In the absence of histology, physicians rely on physical examination, inflammatory markers, and imaging to make the diagnosis. The presence of visible, chronically exposed bone within a forefoot ulcer is diagnostic. The accuracy of a probe to bone test depends on the pretest probability of osteomyelitis. Sensitivity and specificity range from 60% to 87% and from 85% to 91%, respectively.24 For patients with a single forefoot ulcer and PEDIS grade 2 or 3 infection, considering both ulcer depth and serum inflammatory markers (ulcer depth greater than 3 mm, or C-reactive protein greater than 3.2 mg/dL; ulcer depth greater than 3 mm, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate greater than 60 mm/h) increases sensitivity to 100%, although the specificity is relatively low (55% and 60%, respectively).25 When the diagnosis remains uncertain by physical examination, imaging is necessary for further evaluation.

ROLE OF IMAGING

All patients with DFI should have plain radiographs to look for foot deformities, soft tissue gas, foreign bodies, and osteomyelitis. If plain radiographs show classic evidence of osteomyelitis, (ie, cortical erosion, periosteal reaction, mixed lucency, and sclerosis in the absence of neuro-osteoarthropathy), advanced imaging is not necessary. However, these changes may not appear on plain films for up to 1 month after infection onset.15,26

The purpose of advanced imaging in the inpatient management of DFI is to detect conditions not obvious by physical examination or by plain radiographs that would alter surgical management (ie, deep abscess or necrotic bone) or antibiotic duration (ie, osteomyelitis or tenosynovitis).15 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the diagnostic modality of choice when the wound does not probe to bone and the diagnosis remains uncertain27 due to its accuracy and availability.1,15 However, MRI cannot always distinguish between infection and neuro-osteoarthropathy, especially in patients who have infection superimposed on a Charcot foot, have had recent surgical intervention, or have osteosynthesis material at the infection site.24 If MRI is contraindicated, guidelines vary on the next recommended test. The IDSA and the Society for Vascular Surgery recommend a labeled white blood cell scan combined with a bone scan, whereas the IWGDF recommends a labeled leukocyte scan, a single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT/CT), or a fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) scan.1,15,19 A recent comparison of a labeled white blood cell SPECT/CT versus MRI (using histology as the gold standard) reported that SPECT/CT had a similar sensitivity (89% versus 87%, respectively) and specificity (35% versus 37%, respectively) to MRI.28 In practice, physicians should consider which studies are readily available and confidently interpreted by radiologists at their institution.

ASSESSMENT OF ULCER ETIOLOGY

After infection is diagnosed and staged, clinicians should determine the underlying derangement in order to prevent recurrence after discharge. Common derangements leading to ulceration in diabetics include PAD, neuropathy, muscular tension, altered foot mechanics, trauma, or a combination of the above.1,15,29-31 All patients with DFI should undergo pedal perfusion assessment by an ABI, ankle and pedal Doppler arterial waveforms, and either toe brachial index (TBI) or transcutaneous oxygen pressure.1,15,19 In cases of suspected calcification, TBI is a more reliable measure of ischemia compared with the ABI.16,19 For patients with signs and symptoms of ischemia and an abnormal ABI or TBI measurement (ABI <0.9 and TBI <0.7), a nonurgent consultation with a vascular surgeon is recommended, while patients with severe ischemia (ABI <0.4) usually require urgent revascularization.15,32

A sensory examination with a Semmes-Weinstein monofilament should be conducted to identify patients with loss of protective sensation who may benefit from offloading devices and custom orthotics.15 Foot anatomy and mechanics as well as potential Achilles tendon contractures should be evaluated by a foot specialist such as a podiatrist, orthotist, orthopedist, or vascular surgeon, especially if debridement or amputation is being contemplated.

OBTAINING CULTURES

After diagnosing the infection clinically, appropriately obtained cultures are essential to guide therapy in all except mild cases with no prior antibiotic exposure or MRSA risk.1,15 Guidelines strongly recommend that specimens be obtained by biopsy or curettage from deep tissue at the base of the ulcer after the wound has been cleansed and debrided and prior to initiating antibiotics.1,15,33 Aspiration of purulent secretions using a sterile needle and syringe is another acceptable culturing method.15 While convenient, swab cultures are prone to both false-positive and false-negative results.34 Repeat cultures are only needed for patients who are not responding to treatment or for surveillance of resistant organisms.1

In cases of osteomyelitis, bone specimens should be sent for culture and histology either during surgical debridement or a bone biopsy. At the time of debridement, cultures and pathology should be sent from the proximal (clean) bone margin in order to document whether there is residual osteomyelitis postdebridement.35 For patients not planned for debridement, a bone biopsy is recommended if the diagnosis of osteomyelitis is unclear, response to empiric therapy is poor, broad-spectrum antibiotics are being considered, or the infection is in the midfoot or hindfoot.1,15,19 Results from soft tissue or sinus tract specimens should not be used to guide antibiotic selection in osteomyelitis, as several studies suggest that they do not correlate with bone culture results; one retrospective review found a mere 22.5% correlation between wound swabs and bone biopsy.1,36 A 2-week antibiotic-free period prior to biopsy is recommended in order to minimize the risk of false-negative results but must be balanced with the risk of worsening infection.1,15 If possible, the biopsy should be performed through uninfected tissue under fluoroscopy or CT guidance, with 2 to 3 cores obtained for culture and histology.1,15

INTERPROFESSIONAL INPATIENT CARE

A growing number of health systems have created inpatient and/or outpatient interprofessional diabetic foot care teams, and several studies demonstrated an association between these teams and a reduction in major amputations.7-11,13 The goal of the inpatient team is to rapidly triage patients with moderate to severe infections, expedite surgical interventions and culture collection, establish an effective treatment plan, and ensure adherence postdischarge to optimize outcomes. The common core of most teams includes podiatry, endocrinology, wound care, and vascular surgery, but team composition may vary based on the availability of local specialists with interest and expertise in DFI.9,10,33

The division of consultation between podiatry and orthopedic surgery is highly dependent upon individual practice patterns and hospital structure. In general, forefoot ulcers may be managed by podiatry or orthopedic surgery, while severe Charcot deformities are most often treated by orthopedic surgeons. Wound care nurses are often integral to successful wound healing, collaborating across specialties and serving as a weekly or biweekly point of contact for patients.

Early involvement of Infectious Disease (ID) specialists can be useful for guiding antibiotic choices and facilitating follow-up. ID should be involved with patients who require long-term antibiotic therapy (ie, cases of deep-tissue infection that are not completely amputated or debrided), have failed outpatient or empiric therapy, have antibiotic allergies or drug-resistant pathogens, or are being considered for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy.

ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

The duration of antibiotic treatment for DFI is based on the severity of infection and response to treatment (Supplementary Table 3). Treatment should continue until the signs and symptoms of infection resolve, but there is no strong evidence to support treatment through complete healing. Healing will usually occur in 1 to 2 weeks for mild infections and in 2 to 3 weeks for moderate or severe infections.

Traditional management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis has relied almost exclusively on resection of all infected bone. However, data have emerged over the last 10 years to support initial medical management of select patients. Further research regarding the optimal treatment regimen and duration is ongoing, with 1 recent, randomized control trial comparing 6 versus 12 weeks of antibiotics for patients treated medically for osteomyelitis finding no difference in remission rates.1,41 Patients managed surgically for osteomyelitis are often treated parenterally for at least 4 weeks, but this practice is not based on strong evidence, and guidelines suggest most patients could be switched to highly bioavailable oral agents after a shorter course of intravenous therapy.1,15 Guidelines recommend 2 to 5 days of antibiotics after complete resection of infected bone and soft tissue (Supplementary Table 3). If the infected soft tissue remains, 1 to 3 weeks of therapy is usually sufficient, while 4 to 6 weeks is often needed if there is residually infected but viable bone.15

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

In patients with osteomyelitis, the decision between medical and surgical management is complex. Absolute indications for surgical resection include systemic toxicity with associated tissue infection, an open or infected joint space, and patients with prosthetic heart valves.27 However, the need for surgery is unclear beyond these absolute indications, and approximately two-thirds of osteomyelitis cases may be arrested or cured with antibiotic therapy alone.1 A prospective randomized comparative trial of patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis found that patients treated with 90 days of antibiotics had similar healing rates, times to healing, and short-term complications as compared with those who underwent conservative bone resection.44 While further research is needed to determine which types of patients with osteomyelitis may be successfully treated without surgery, the IWGDF, the IDSA, and osteomyelitis experts have offered guidance on this decision (Table 2).1,15,27 If resection is necessary, hospitalists should request at least 4 specimens to help guide postoperative antibiotic therapy (1 sample for histology and 1 for microbiology, at both the grossly abnormal bone and the bone margin), as negative margin cultures predict a lower relapse risk for infection.1,35

CRITERIA FOR DISCHARGE

Guidelines suggest that patients be clinically stable before discharge, complete any urgent surgery, achieve acceptable glycemic control, and be presented with a comprehensive outpatient plan, including antibiotic therapy, offloading, wound care instructions, and outpatient follow-up (Supplementary Table 4). Physicians must consider patient and family preferences, expected adherence to therapy, availability of home support, and payer and cost issues when creating the discharge plan.15

INTERPROFESSIONAL OUTPATIENT CARE

An effective outpatient care team is critical to ensure wound healing and infection resolution. Efforts should be made to discharge patients to a comprehensive outpatient interprofessional foot care team, with a plan that includes professional foot care, patient education, and adequate footwear.48 Team composition varies but often includes representatives from vascular surgery, podiatry, orthotics, wound care, endocrinology, orthopedics, physical therapy and rehabilitation, infectious disease, and dermatology.11-13

CONCLUSION

DFIs are a common cause of morbidity in patients with diabetes and result in significant costs to the US healthcare system. Hospitalized patients with a DFI require appropriate classification of wound severity and assessment of vascular status, protective sensation, and potential osteomyelitis. Inpatient management of these patients includes obtaining necessary cultures, choosing an antibiotic regimen based on infection severity and the likely causative agent, and evaluating the need for surgical intervention. Prior to discharge, providers should determine a comprehensive follow-up plan and ensure patient engagement. Finally, interprofessional management has been shown to improve outcomes in DFI and should be adopted in both the inpatient and outpatient settings.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.