Which patients with pulmonary embolism need echocardiography?

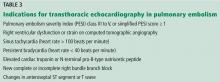

Most patients admitted with pulmonary embolism (PE) do not need transthoracic echocardiography (TTE); it should be performed in hemodynamically unstable patients, as well as in hemodynamically stable patients with specific elevated cardiac biomarkers and imaging features.

The decision to perform TTE should be based on clinical presentation, PE burden, and imaging findings (eg, computed tomographic angiography). TTE helps to stratify risk, guide management, monitor response to therapy, and give prognostic information for a subset of patients at increased risk for PE-related adverse events.

RISK STRATIFICATION IN PULMONARY EMBOLISM

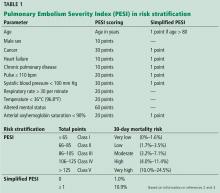

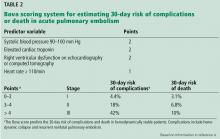

PE has a spectrum of presentations ranging from no symptoms to shock. Based on the clinical presentation, PE can be categorized as high, intermediate, or low risk.

High-risk PE, often referred to as “massive” PE, is defined in current American Heart Association guidelines as acute PE with sustained hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes or requiring inotropic support), persistent profound bradycardia (heart rate < 40 beats per minute with signs or symptoms of shock), syncope, or cardiac arrest.1

Intermediate-risk or “submassive” PE is more challenging to identify because patients are more hemodynamically stable, yet have evidence on electrocardiography, TTE, computed tomography, or cardiac biomarker testing—ie, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or troponin—that indicates myocardial injury or volume overload.1

Low-risk PE is acute PE in the absence of clinical markers of adverse prognosis that define massive or submassive PE.1

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC FEATURES OF HIGH-RISK PULMONARY EMBOLISM

Certain TTE findings suggest increased risk of a poor outcome and may warrant therapy that is more invasive and aggressive. High-risk features include the following:

- Impaired right ventricular function

- Interventricular septum bulging into the left ventricle (“D-shaped” septum)

- Dilated proximal pulmonary arteries

- Increased severity of tricuspid regurgitation

- Elevated right atrial pressure

- Elevated pulmonary artery pressure

- Free-floating right ventricular thrombi, which are associated with a mortality rate of up to 45% and can be detected in 7% to 18% of patients6

- Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, an echocardiographic measure of right ventricular function1; a value less than 17 mm suggests impaired right ventricular systolic function7

- The McConnell sign, a feature of acute massive PE: akinesia of the mid-free wall of the right ventricle and hypercontractility of the apex.

These TTE findings often lead to treatment with thrombolysis, transfer to the intensive care unit, and activation of the interventional team for catheter-based therapies.1,8 Free-floating right heart thrombi or thrombus straddling the interatrial septum (“thrombus in transit”) through a patent foramen ovale may require surgical embolectomy.8