Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

From the Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of vascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

- Methods: Literature and guidelines were reviewed and the evidence is presented around a clinical case.

- Results: T2DM has a high prevalence and confers significant lifetime risk for macrovascular disease, including stroke, heart disease, and peripheral arterial disease. There is strong evidence to support nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation and weight loss, and pharmacologic interventions, such as statin therapy, in order to decrease lifetime risk. The effectiveness of an intervention as well as the strength of the evidence supporting an intervention differs depending on the stage of the disease.

- Conclusion: Once a patient is diagnosed with T2DM, it is important to recognize that their lifetime risk for vascular disease is high. Starting at this stage and continuing throughout the disease course, cardiovascular risk should be assessed in an ongoing manner and evidence-based interventions should be implemented whenever they are indicated. Using major guidelines as a framework, we provide an evidence-based approach to the reduction of vascular risk in these patients.

Key words: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, prevention, risk assessment, risk factors.

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is considered epidemic in the developed world, and is rapidly increasing in the developing world. Since 1980, there has been a near quadrupling of the number of adults with diabetes worldwide to an estimated 422 million in 2014 [1]. Because diabetes affects the whole body vascular system, there is a significant burden of vascular complications directly attributable to diabetes. Although the rates of diabetes-related complications are declining, the burden of disease remains high due to the increasing prevalence of diabetes [2]. The tremendous burden of diabetes and its complications on the population make it imperative that all health care practitioners understand the vascular effects of diabetes as well as evidence-based interventions that can mitigate them. In this review, we present an approach to the assessment, prevention, and treatment of cardiovascular disease in patients with T2DM.

Case Study

A 38-year-old male presents to his family physician’s office for a routine check-up. He is obese and a smoker, has no other health issues, and is taking no medications. He is sent for routine bloodwork and his A1c and fasting glucose are elevated and are diagnostic for diabetes. He returns to the clinic to discuss his results.

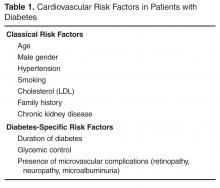

How are cardiovascular risk and risk factors assessed in a patient with diabetes?

There are many risk scores and risk calculators available for assessing cardiovascular risk. The Framingham Risk Score is the most commonly employed and takes into account the most common risk factors for cardiovascular risk, including cholesterol level, age, gender, and smoking status. Unfortunately, because a patient with diabetes may have a high lifetime risk but low or moderate short-term risk, these risk scores tend to underestimate overall risk in the population with diabetes [3,4]. Furthermore, since early intervention can decrease lifetime risk, it is important to recognize the limitations of these risk scores.

What interventions should be used for primary prevention at this stage?

A number of interventions can decrease lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease in persons with diabetes. First, smoking increases risk for all forms of vascular disease, including progression to end-stage renal disease, and is an independent predictor of mortality. Smoking cessation is one of the most effective interventions at decreasing these risks [6]. Second, lifestyle interventions such as diet and exercise are often recommended. The Look AHEAD trial studied the benefits of weight loss and exercise in the treatment of T2DM through a randomized control trial involving more than 5000 overweight patients with T2DM. Patients were randomly assigned to intensive lifestyle interventions targeting weight loss or a support and education group. Although the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial did not demonstrate clinical outcome benefit with this intensive intervention, there was improvement in weight, cholesterol level, blood pressure, and glycemic control, and clinical differences may have been related to study power or differences in cardioprotective medication use [7]. Furthermore, at least 1 large randomized trial of dietary intervention in high-risk cardiovascular patients, half of whom had diabetes (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea [PREDIMED]), showed significant benefits in cardiovascular disease, reducing the incidence of major cardiovascular events [8]. According to most diabetes guidelines, diet and exercise continue to be stressed as initial management for all patients with diabetes [9–12].

In addition, although intensive glucose control decreases microvascular complication rates, it has been more difficult to demonstrate a reduction in cardiovascular disease with more intense glycemic control. However, long-term follow-up of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) cohort, a population that was earlier in their diabetes course, clearly demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular events and mortality with better glycemic control over the long term [13,14]. For those who are later in their diabetes course, meta-analyses of glycemic control trials, along with follow-up studies, have also shown that better glycemic control can reduce cardiovascular events, but not mortality [15–17]. Therefore, glucose lowering should be pursued for cardiovascular risk reduction, in addition to its effects on microvascular complications.

It is well established that a multifactorial approach to cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes is effective. In the Steno-2 study, 160 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to receive multidisciplinary, multifactorial intensive target-based lifestyle and pharmacologic intervention or standard of care. The intensive therapy group all received smoking cessation counseling, exercise and dietary advice, vitamin supplementation, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) was added for all patients with clinical macrovascular disease. Dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia were all treated in a protocolized way if lifestyle interventions did not achieve strict targets. During the mean 7.8 years of follow-up, the adjusted hazard ratio for a composite of cardiovascular death and macrovascular disease was 0.47 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.22 to 0.74; P = 0.01) [18]. These patients were followed for an additional 5.5 years in an observational study with no further active intervention in both groups. Over the entire period, there was an absolute risk reduction of 20% for death from any cause, resulting in a number needed to treat of 5 for 13 years [19]. As a result of these compelling data, guidelines from around the world support a multifactorial approach, with the Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) guidelines [20] promoting the use of the “ABCDES” of vascular protection:

A – A1C target

B – Blood pressure target

C – Cholesterol target

D – Drugs for vascular protection

E – Exercise/Eating

S – Smoking cessation

Is any particular dietary pattern recommended?

There is a large and ever-growing number of dietary patterns that are marketed to improve weight and cardiovascular health. Unfortunately, however, few of these interventions have been studied rigorously, and most dietary interventions are found to be unsustainable in the long term. In the case of motivated patients, there are some specific dietary patterns with high-quality evidence to recommend them. The simplest intervention is the implementation of a vegetarian or vegan diet. Over 18 months, this has been shown to improve fasting glucose and cholesterol profile, and promote weight loss [21]. In another study, a calorie-restricted vegetarian diet led to a reduction in diabetes medication in 46% of participants (versus 5% with conventional diet) [22].

A Mediterranean diet is comprised of large amounts of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains. In addition, it includes moderate consumption of olive oil, dairy, fish and poultry, with low consumption of red meat. This dietary pattern has been extensively studied, and in a meta-analysis has been shown to improve glycemic control, blood pressure, and lipid profile [23]. The PREDIMED study evaluated the efficacy of 2 versions of the Mediterranean diet, one supplemented with olive oil or mixed nuts, for reducing cardiovascular events. This multicenter randomized control trial of 7447 participants at high cardiovascular risk (48.5% of whom had diabetes) was stopped early due to benefit. Both versions of the diet reduced cardiovascular events by 30% over 5 years of follow-up [8].

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is similar to the Mediterranean diet in focusing on fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, whole grains, nuts, fish, and poultry, while avoiding red meat. In addition, it explicitly recommends avoiding sweets and sweetened beverages, as well as dietary fat. In a trial of patients with diabetes matched for moderate sodium intake, the DASH diet has been shown to decrease A1c, blood pressure, and weight and improve lipid profile within 8 weeks [24,25].

In addition to these specific dietary patterns, specific foods have been shown to improve glycemic control and cardiovascular risk profile, including mixed unsalted nuts, almonds, dietary pulses, and low-glycemic versus high-glycemic index carbohydrates [26–31].

In accordance with CDA, American Diabetes Association (ADA), and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) guidelines, we recognize that a variety of diets can improve the cardiovascular risk profile of a patient [12,32,33]. Therefore, we suggest a tailored approach to dietary changes for each individual patient. This should, whenever possible, be undertaken with a registered dietitian, with emphasis placed on the evidence for vascular protection, improved risk profile, patient preference, and likelihood of long-term sustainability.

Should therapy for weight loss be recommended for this patient?

There are currently a number of effective strategies for achieving weight loss, including lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and surgery. The evidence base for dietary interventions for diabetes is reviewed above. The Look AHEAD study randomized 5145 overweight or obese patients with T2DM to intensive lifestyle intervention for weight loss through promotion of decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity, or usual diabetes support and education. After a median follow-up of 9.6 years, the study was stopped early on the basis of a futility analysis despite greater weight loss in the intervention group throughout the study. However, other benefits were derived including reduced need for medications, reduced sleep apnea, and improved well-being [7].

Pharmacotherapy agents for weight loss have been approved by various regulatory agencies. None has as yet shown a reduction in cardiovascular events. Therefore, these cannot be recommended as therapies for vascular protection at this time.

Bariatric surgery is an effective option for weight loss in patients with diabetes, with marked and sustained improvements in clinically meaningful outcomes when compared with medical management. The longest study of bariatric surgery is the Swedish Obesity Study, a prospective case-control study of 2010 obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery and 2037 matched controls. After a median of 14.8 years of follow-up, there was a reduction in overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.71) and decreased incidence of diabetes (HR 0.17), myocardial infarction (HR 0.71), and stroke (HR 0.66). Diabetes remission, defined as normal A1c off of anti-hyperglycemic therapy, was increased at 2 years (odds ratio [OR] 13.3) and sustained at 15 years (OR 6.3) [34–36]. Randomized controlled trials of bariatric surgery have thus far been small and do show some decreases in cardiovascular risk factors [37–40]. However, these have not yet been of sufficient duration or size to demonstrate a decrease in cardiovascular event rate. Although local policies may vary in referral recommendation, the Obesity Society, ADA, and CDA recommend that patients with a body mass index greater than 40 kg/m2, or greater than 35 kg/m2 with an obesity-related comorbidity such as diabetes, should be referred to a center that specializes in bariatric surgery for evaluation [41–43].