Distress management in cancer patients in Puerto Rico

This article documents the process of developing and implementing distress management at HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital in Caguas, Puerto Rico, and summarizes the results of a pilot study to validate the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a measure to improve the process of emotional distress management in particular. The information is illustrative and useful for medical institutions looking to comply with the American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer accreditation standard #3.2, regarding psychosocial distress screening.

Accepted December 20, 2016. Correspondence Maricarmen Ramírez-Solá; mariramirez@himapr.com. Disclosures The author reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

JCSO 2017;15(2):68-73. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications. doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0321.

A comprehensive, patient-centered approach is required to accomplish cancer best standards of care.1 This approach reflects the holistic conceptualization of health in which the physical, emotional, and social dimensions of the human being are considered when providing medical care. As a result, to look after all patient needs, interdisciplinary and well-coordinated interventions are recommended. Cancer patients should be provided not only with diagnostic, treatment, and follow-up clinical service, but also with the supportive assistance that may positively influence all aspects of their health.

To appraise physical, social, emotional and spiritual issues and to develop supportive interventional action plans, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends screening all cancer patients for distress.2 In particular, screening the emotional component of distress occupies a prominent place in this process because it is now recognized as the sixth vital sign in oncology.3 Even though the influence of emotional distress over cancer mortality rates and disease progression is still under scrutiny,4 its plausible implications over treatment compliance have been pointed out. Patients with higher levels of emotional distress show lower adherence to treatment and poorer health outcomes.5 Furthermore, prevalence rates of emotional distress in cancer patients from ambulatory settings6 and oncology surgical units have been studied and have provided justification for distress management.7 Studies have shown low ability among oncologists to identify patients in distress and oncologists’ tendency to judge distress higher than the patients themselves.8 As a consequence, to achieve systematic distress evaluations and appropriate referrals for care, guidelines for distress management should be implemented in clinical settings. It is recommended that tests are conducted to find brief screening instruments and procedures to assure accurate interventions according to patient specific needs.

This article presents the process of implementing a distress management program at HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital in Caguas, Puerto Rico, with particular emphasis on the management of emotional distress, which has been defined as the feeling of suffering that cancer patients may experience after diagnosis. In addition, we have included data from a pilot study that was completed for content validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to estimate depression levels in Puerto Rican cancer patients.

,Methods

HIMA-San Pablo operates a group of privately owned hospitals in Puerto Rico. It established a cancer center in Caguas in 2007, recruiting a multispecialty medical faculty to provide cancer care and bone marrow transplants for adult and pediatric patients. The cancer center, currently named HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital (HSPOH), is a hospital within a hospital licensed by the Puerto Rico Department of Health. In 2007, a cancer committee was established as the steering committee to ensure the delivery of cancer care according to best standards of care. The committee took responsibility for developing all activities needed to achieve the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation under the category of Comprehensive Community Cancer Center. The committee established a psychosocial team to develop a protocol for the delivery of distress management for adult patients. (The psychosocial needs of pediatric patients are assessed through other procedures.)

To develop the protocol, principles of input-output model of research and quality analysis in health care were applied.9 The input-output model, with its origin in engineering, helped map systematic activities to transform empirical data on cancer psychosocial care into operational procedures. Focus was given to data gathering (input), information organization and analysis (throughput), and the schematization of emotional distress management care (output).

The input phase

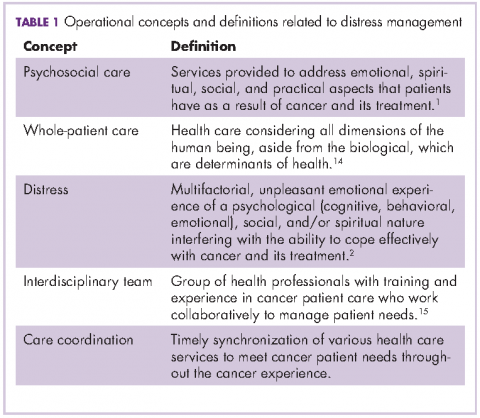

In the input phase, elements of psychosocial care and operational definitions related to distress management in general were identified through literature review (Table 1). Basic parameters for distress management were clarified, resulting in a conceptual framework based in four remarks: First, according to NCCN, distress is a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social, and spiritual nature. It may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its symptoms and its treatment. Its intensity may fluctuate from feelings of suffering and fear to incapacitating manifestations of anxiety and depression2 and its severity may hamper patient quality of life and treatment compliance.

Second, distress management requires the intervention of an interdisciplinary team with both medical and allied health professionals. This may include mental health specialists and other professionals with training and experience in cancer-related issues, who work with reciprocal channels of communication for the exchange of patient information.

Third, NCCN recommends using the Distress Thermometer for patient initial distress screening.10-12 It consists of a numeric scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (severe distress) in which patients classify their level of distress. The numeric scale is followed by a section in which patients identify areas of practical, familiar, emotional, spiritual/ religious, and physical concerns. Based on responses, interviews may follow to set distress management interventions.

Fourth, screening and assessment are different but sequential and complementary stages of distress management. Screening is viewed as a rapid strategy to identify cancer patients in distress. Assessment looks out for a broader appraisal and documentation of factors with repercussions over patient distress level and resiliency capability.13 In many instances, the patient’s emotional distress is better understood in the assessment phase.