What you can do for your fibromyalgia patient

ABSTRACT

Patients with fibromyalgia typically have pain “all over,” tender points, generalized weakness and fatigue, nonrestorative sleep, and a plethora of other symptoms. In contrast to inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, laboratory tests and physical examination findings are usually normal. American College of Rheumatology guidelines facilitate diagnosis. Management requires a multifaceted, long-term strategy that emphasizes improving function rather than reducing pain.

KEY POINTS

- Fibromyalgia is a clinical diagnosis, and specialized testing beyond basic laboratory tests is not indicated.

- Antinuclear antibody test results can be confusing, and the test should not be ordered unless a patient has objective features suggesting systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Treatment should be tailored to comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance. Options include serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, duloxetine), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline), and gabapentinoids (pregabalin or gabapentin). These drugs can be used singly or in combination.

- Medications that do not work should be discontinued.

- “Catastrophizing” by the patient is common in fibromyalgia and can be addressed by education, cognitive behavioral therapy, and anxiolytic or antidepressant drugs.

- Sustained, lifelong exercise is the treatment strategy most associated with improvement.

DISCUSSION: CHARACTERIZING PAIN

Understanding categories of pain syndromes can help us understand fibromyalgia. Pain can be categorized into 3 types that sometimes overlap2:

Nociceptive or peripheral pain is related to damage of tissue by trauma or inflammation. Syndromes include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE.

Neuropathic pain is associated with damage of peripheral or central nerves. Examples are neuropathy from herpes, diabetes, or spinal stenosis.

Centralized pain has no identifiable nerve or tissue damage and is thought to result from persistent neuronal dysregulation, overactive ascending pain pathways, and a deficiency of descending inhibitory pain pathways. There is evidence of biochemical changes in muscles, possibly related to chronic ischemia and an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Dysregulation of the sympathoadrenal system and hypothalamic-pituitary axis has also been implicated. And genetic predisposition is possible. Examples of centralized pain syndromes include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic pain syndrome, neurogenic bladder, and interstitial cystitis.

Clues to a centralized pain syndrome

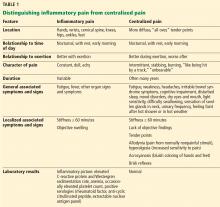

For patients with suspected fibromyalgia, distinguishing peripheral pain from centralized pain can be a challenge (Table 1). For example, SLE does not cause inflammation of the spine, so neck or back pain is not typical. Although both nociceptive and centralized pain syndromes improve with exertion, only patients with centralized pain are typically exhausted and bedbound for days after activity. Patients with centralized pain tend to describe their pain in much more dramatic language than do patients with inflammatory pain. Centralized pain tends to be intermittent; inflammatory pain tends to be constant. Patients with centralized pain often have had pain for many years without a diagnosis, but this is rare for patients with an inflammatory condition.

A patient with fibromyalgia typically has a normal physical examination, although allodynia (experiencing pain from normally nonpainful stimulation), hyperalgesia (increased pain perception), and brisk reflexes may be present. Fibromyalgia may involve discoloration of the fingertips resulting from an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Laboratory results are typically normal with fibromyalgia.

Patients with either nociceptive or centralized pain report stiffness, but the cause likely differs. We typically think of stiffness as arising from swollen joints caused by inflammation, but stiffness can also be caused by abnormally tight muscles, as occurs in fibromyalgia.

FIBROMYALGIA IS A CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosing fibromyalgia does not require multiple laboratory and imaging tests. The key indicators are derived from the patient history and physical examination.

Diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia published by the American College of Rheumatology have evolved over the years. The 2011 criteria, in the form of a self-reported patient questionnaire, have 2 components3:

- The Widespread Pain Index measures the extent of pain in 19 areas.

- The Symptom Severity scale assesses 3 key symptoms associated with fibromyalgia, ie, fatigue, cognitive problems, and nonrestorative sleep (scale of 0–3 for each symptom).

There are also questions about symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, depression, and headache.

Fibromyalgia is diagnosed if a patient reports at least 7 painful areas and has a symptom severity score of at least 5. A patient may also meet the 20113 and the 2016 criteria4 if he or she has 4 painful areas and the pain is perceived in 4 of 5 areas and the Symptom Severity Scale score is 9 or higher.4 This questionnaire is not only a rapid diagnostic tool for fibromyalgia, it also helps identify and focus on specific issues—for example, having severe pain in a few localized areas, or having headache as a predominant problem.

These criteria are useful for a variety of patients, eg, a patient with hip arthritis may score high on the questionnaire, indicating that a component of centralized pain is also present. Also, people who have undergone orthopedic surgery who score high tend to require more narcotics to meet the goals of pain improvement.

The 2016 criteria,4 the most recent, maintain that pain must be generalized, ie, present in at least 4 of 5 body areas. They also emphasize that fibromyalgia is a valid diagnosis irrespective of other conditions.

CASE 1 CONTINUED: THE PATIENT REJECTS THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient meets the definition of fibromyalgia by each iteration of the American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria. She also has generalized anxiety disorder and a positive ANA test. She is advised to participate in a fibromyalgia educational program, start an aerobic exercise program, and consider taking an antidepressant medication with anxiolytic effects.

However, the patient rejects the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. She believes that the diagnosis of SLE has been overlooked and that her symptom severity is being discounted.

In response, the rheumatologist orders additional tests to evaluate for an autoimmune disorder: extractable nuclear antigen panel, complement C3 and C4, double-stranded DNA antibodies, and protein electrophoresis. Results are all in the normal range. The patient is still concerned that she has SLE or another autoimmune disease because of her abnormal ANA test result and remains dissatisfied with her evaluation. She states that she will complain to the clinic ombudsman.

SIGNIFICANCE OF ANA TESTING

Patients with positive test results increasingly go online to get information. The significance of ANA testing can be confusing, and it is critical to understand and be able to explain abnormal results to worried patients. Following are answers to some common questions about ANA testing:

Is ANA positivity specific for SLE or another autoimmune disease?

No. ANA is usually tested by indirect immunofluorescence assay on HEp-2 cells. The test can identify about 150 antigens targeted by antibodies, but only a small percentage are associated with an autoimmune disease, and the others do not have a known clinical association. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) ANA testing is also available but is considered less sensitive.

Abeles and Abeles5 retrospectively assessed 232 patients between 2007 and 2009 who were referred to rheumatologists for evaluation because of an elevated ANA test result. No ANA-associated rheumatic disease was found in patients who had a result of less than 1:160, and more than 90% of referrals for a positive ANA test had no evidence of ANA-associated disease. The positive predictive value was 9% for any connective tissue disease, and only 2% for SLE. The most common reason for ordering the test was widespread pain (23%). The authors concluded that ANA testing is often ordered inappropriately for patients with a low pretest probability of an ANA-associated rheumatic disease.

Screening with ANA testing generates many false-positive results and unnecessary anxiety for patients. The prevalence of SLE in the general population is about 0.1%, and other autoimmune diseases total about 5% to 7%. By indirect immunofluorescence assay, using a cutoff of 1:80 (the standard at Cleveland Clinic), about 15% of the general population test positive. By ELISA, with a cutoff of 20 ELISA units, 25% of healthy controls test positive.

It is true that ANA positivity may precede the onset of SLE.6,7 Arbuckle et al8 evaluated serum samples from the US Department of Defense Serum Repository obtained from 130 people before they received a diagnosis of SLE; in 115 (88%), at least 1 SLE-related autoantibody was present before diagnosis (up to 9.4 years earlier). However, in those who test positive for ANA, the percentage who eventually develop autoimmune disease is small.5