Disparities in cervical cancer in African American women: What primary care physicians can do

ABSTRACT

African American women are disproportionately affected by cervical cancer, with higher rates of incidence and mortality than white women. Most of the difference would disappear with equal treatment. As usual, primary care providers are on the front lines.

What is in a genotype?

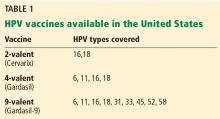

HPV is implicated in progression to both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Worldwide, HPV genotypes 16 and 18 are associated with 73% of cases of invasive cervical cancer; most of the remainder are associated with, in order of decreasing prevalence, genotypes 58, 33, 45, 31, 52, 35, 59, 39, 51, and 56.21

High-grade cervical lesions in African American women may less often be positive for HPV 16 and 18 than in white women.22,23 On the other hand, the proportion of non-Hispanic black women infected with HPV 35 and 58 was significantly higher than in non-Hispanic white women.22 Regardless, HPV screening is recommended for women of all races and ethnicities.

The 2-valent and 4-valent HPV vaccines do not cover HPV 35 or 58. The newer 9-valent vaccine covers HPV 58 (but not 35) and so may in theory decrease any potential disparity related to infection with a specific oncogenic subtype.

THE ROLE OF PREVENTION

HPV vaccination

The Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease study demonstrated that the 4-valent vaccine was highly effective against cervical intraepithelial neoplasia due to HPV 16 and 18.24 In another study, the 2-valent vaccine reduced the incidence of CIN 3 or higher by 87% in women who received all 3 doses and who had no evidence of HPV infection at baseline.25

HPV vaccination is expensive. Each shot costs about $130, plus the cost of administering it. Although the Vaccines for Children program covers the HPV vaccine for uninsured and underinsured children and adolescents under age 19, Medicaid coverage varies from state to state for adults over age 21.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)26 recommends routine vaccination for:

- Males 11 or 12 years old

- Females ages 9 to 26.

In October 2016, the ACIP approved a 2-dose series given 6 to 12 months apart for patients starting vaccination at ages 9 through 14 years who are not immunocompromised. Others should receive a 3-dose series, with the second dose given 1 to 2 months after the first dose and the third dose given 6 months after the first dose.27 Previously, 3 doses were recommended for everyone.

Disparities in HPV vaccination rates

HPV vaccination rates among adolescents in the United States increased from 33.6% in 2013 to 41.7% in 2014.28 However, HPV vaccination rates continue to lag behind those of other routine vaccines, such as Tdap and meningococcal conjugate.

Reagan-Steiner et al28 reported that more black than white girls age 13 through 17 received at least 1 dose of a 3-dose HPV vaccination series, but more white girls received all 3 doses (70.6% vs 61.6%). In contrast, a meta-analysis by Fisher et al29 found African American and uninsured women generally less likely to initiate the HPV vaccination series. Kessels et al30 reported similar findings.

Barriers to HPV vaccination

Barriers to HPV vaccination can be provider-dependent, parental, or institutional.

Malo et al31 surveyed Florida Medicaid providers and found that those who participated in the Vaccines for Children program were less likely to cite lack of reimbursement as a barrier to vaccination.

Meites et al32 surveyed sexually transmitted disease clinics and found that common reasons for not offering HPV vaccine were cost, staff time, and difficulty coordinating follow-up visits to complete the series.

Providers report lack of urgency or lack of perception of cervical cancer as a true public health threat, safety concerns regarding the vaccine, and the inability to coadminister vaccines as barriers.33

Studies have shown that relatively few parents (up to 18%) of parents are concerned about the effect of the vaccine on sexual activity.34 Rather, they are most likely to cite lack of information regarding the vaccine, lack of physician recommendation, and not knowing where to receive the vaccine as barriers.35,36

Guerry et al37 determined that the single most important factor in vaccine initiation was physician recommendation, a finding reiterated in other studies.35,38 A study in North Carolina identified failure of physician recommendation as one of the missed opportunities for vaccination of young women.39

Therefore, the primary care physician, as the initial contact with the child or young adult, holds a responsibility to narrow this gap. In simply discussing and recommending the vaccine, physicians could increase vaccination rates.

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

Although 80% of women will be infected with HPV in their lifetime, only a small proportion will develop cervical cancer, suggesting there are other cofactors in the progression to cervical cancer.40

Given the infectious etiology of cervical cancer, other contributing reproductive health factors have been described. As expected, the number of sexual partners correlates with HPV infection.41,42 Younger age at first intercourse has been linked to development of cervical neoplasia, consistent with persistent infection leading to neoplasia.41,42

Primary care physicians should provide timely and comprehensive sexual education, including information on safe sexual practices and pregnancy prevention.

Human immunodeficiency virus

In 2010, the estimated rate of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in African American women was nearly 20 times greater than in white women.43 Previous studies have shown a clear relationship between HIV and HPV-associated cancers, including cervical neoplasia and invasive cervical cancer.44,45

Women with HIV should receive screening for cervical cancer at the time of diagnosis, 6 months after the initial diagnosis, and annually thereafter.46

Conflicting evidence exists regarding the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of HPV-related disease, so aggressive screening and management of cervical neoplasia is recommended for women with HIV, regardless of CD4+ levels or viral load.47–49